We know that it is possible to learn a language using a dictionary, a grammar or by taking a course. As we dedicate more time, we learn words, a basic vocabulary and sufficient pronunciation to enable us to understand and speak. We all learned the mother tongue of our family when we were toddlers, but only very few of us looked for the meaning of this language, and of its importance in influencing our lives. To undertake this search is to embark on an exceptional journey which can transform our entire life. This is a journey I have lived in investigating the words of my own language, Nehluen.

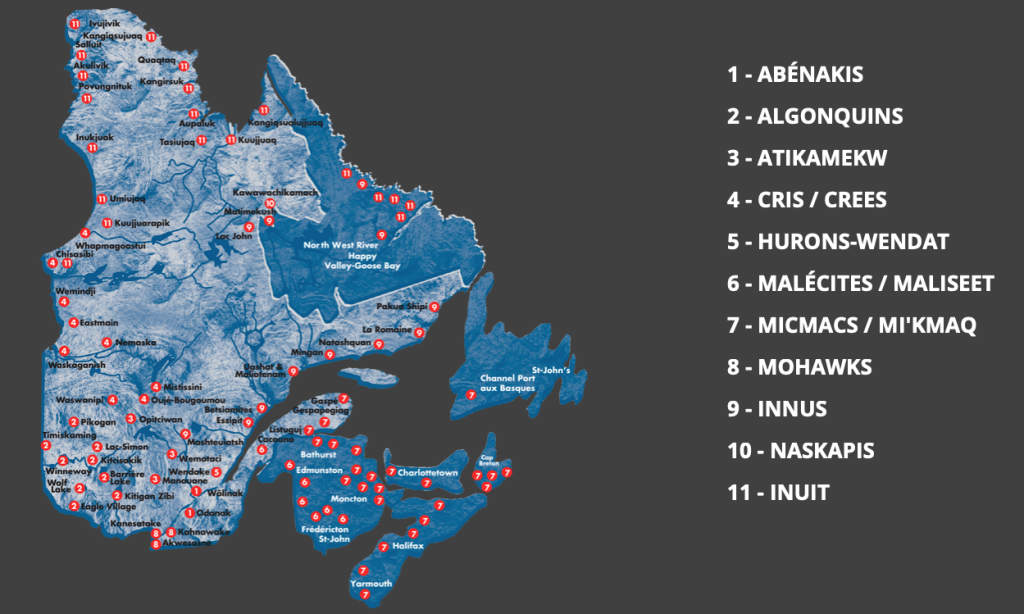

This is the common language used throughout the Innu communities in the province of Quebec, Canada, from Lac St-Jean to Labrador, passing by the lower Côte Nord. The Innu alphabet is based on 11 consonants and 7 vowels. It is indeed a complex language to learn by a new student, but so rewarding because it is so pictorial. The words represent more than a simple concept; they create a picture, a scene, animate a thought, define a precise action linking it with the environment. The Innu words are very exact, descriptive, and full of life.

The underlying reason is that there is one vocabulary adapted for village life and another one for the bush. These nuances are linked with the corresponding environment, which itself is indissociable from thought, and therefore the verbal expression. Since the landscape changes as we move from the South to the North, and from the East to the West, we also see it is reflected in the words used to designate the specific features of each place. It is in fact this precision of the words that enables us to understand the relationships which exist between the flora, fauna and the animals who live there. The human being must adapt to the decor, as he is a part of it. He is included in this big circle where interdependence prevails.

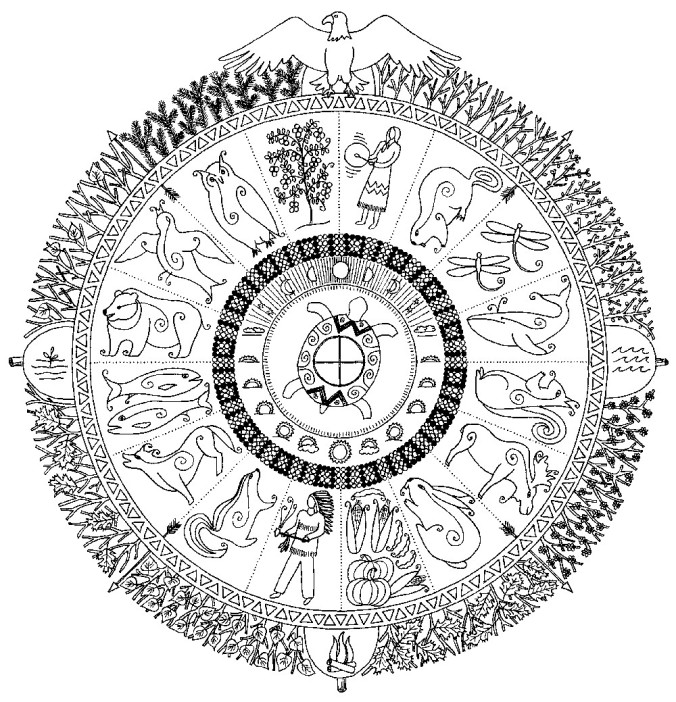

To better understand the base of the Innu language, we have to position ourselves in the context of circular thought. A human being and his environment are indissociable in this kind of thought. The pronoun ‘we’ will serve as an example to better understand the possible shades. If I wanted to speak of ‘we’ which includes me and you (singular or plural), then I would use ‘TSHINANU’. The prefix ‘TSHI-‘ corresponds to you in all its forms. If I wanted to speak about ‘we’ but in a way which is excluding you, whether singular or plural, I would say ‘NINAN’ (with the accent on the second N). Tshinanu – the inclusive form of we – invites sharing, community life, as there are no fences in the word tshinanu. It is a collective ‘we’, an open hand extended to others, inviting them to be a part of the circle. It also correspondingly tells a story, the story of the community of life of the person who speaks or writes. This word brings into relation the land, the animals, the plants and the peoples in the same pronoun.

The exclusive ‘we’ (NINAN) represents the person who is speaking about something, but without the listener or the group of listeners. Take, for example, a hunter who speaks about the moment when he was alone with the deer. He’ll say NINAN because, of course, the listeners weren’t there with him at that exact moment with the deer. The precision of the word thus conveys a very clear picture of the message, defining the role of everyone in the described scene. Speaking a language is a lot more than using words, as it also defines identity and belonging. It draws a portrait of the person’s native origin.

To speak of the area in Quebec inhabited by the Innu peoples, we use the word Nitassinan (our land), which also speaks to our inside land, our roots. For the traditional land of our families in the bush we say Nutshimit. It represents the land of silence, the inside discourse, the place of personal discovery, without any pressure. When presenting oneself and giving the name of the person’s community, people have an idea of the individual through the territory, which in turn speaks of a particular culture and way of life of the people living there, whether nomadic or sedentary.

When an Innu person is cut off from his/her territory, it deeply severs the bond to his/her identity. It means a loss of living roots, like becoming a stranger to him or herself. As a result, the words, loaded with context, lose their bearings in the new environment, there is no more silence, there are no roots. It is exactly this kind of broken bond, this deep wound that best describes placing indigenous peoples in reserves and residential schools, and healing will only be found by a return to the tradition. Let’s remember that the survival of our nations following these traumatic events rests on the shoulders of our elders who proudly protected our culture through the oral tradition. Our environment is the land, the forest, the plants, the insects, the animals, the water, the air and the human beings who are the stewards of the creator’s gift. An interdependent circle of life. From generation to generation, our teachings say that the earth doesn’t belong to us, but rather we belong to her, bearing in her our own distinctive roots.

Tshinashkumitin Iame

Missinak Kameltoutasset

A community celebration in Mashteuiatsh, Quebec in 2018

Marie-Emilie leads the ‘blanket exercise’ to engage people with the experiences of First Nations people.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- Learn more about the Innu people from the Canadian Encyclopedia