Yii means trees, wood and medicinal plants. Yii as trees are crucial for finding the way in the bush and are our main food sources, yii as wood is essential for making most of our tools and instruments, and yii is also the name of our medicinal plants.

Until recently, children from an early age accompanied their parents on hunting and collecting parties in the bush. During these trips, they were taught to observe and remember the trees in order to be able to find their way back home. Trees, such as Manketti, Peeling Bark Ochna, Monkey Orange, Sand Apple and many others produce our most important bushfood.

Yii is also the wood from which we make our tools, such as the handle of the axes and hoes, the clapping wood instruments, the mortars and pestles; we also build our houses with yii.

Medicinal plants are also yii and because of that we call our healers yii khoe ‘yii people’ or yii kx’ao ‘powerful yii people’.

This work (text and photographs) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- I Newspaper reports from South Africa on Katrina Esau’s tireless efforts to preserve her indigenous click-rich language – N/uu

- BBC Travel takes you on a journey to the Northern and Western Cape of South Africa, including to the !Khwa ttu San Heritage Centre. Learn more about our work on N/uu spoken in the Northern Cape here.

Tuuca Orodji

The few thousand Khwe are one of the hunter-gatherer communities who until very recently lived by foraging in their ancestral hunting grounds in the north-eastern part of present-day Namibia. Some decades ago, these areas were declared a game reserve and since then the Khwe are no longer allowed to hunt; even the traditional gathering of bush food has been severely restricted. At the same time, farmers enter the former hunting-grounds of the Khwe with their cattle and destroy the natural resources – the water pans and the trees – both key to the livelihood of the Khwe community and the wild animals.

In the semi-arid land of the Khwe, tuuca orodji ‘rainwater pans’ are the most important water resources in the bush. Members of the Khwe community share their insights and worldviews on them in Khwedam with Living-Language-Land. In the video, a Khwe elder talks about these pans and their significance for the lives of the community. He also describes the threats to the existence of these pans by massive in-migration of farmers and their cattle, who destroy many of these water resources, which were essential for the traditional livelihood of the Khwe and which are still vital for the survival of the elephants and other wild animals in this area.

This work (text and photographs) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Itrofillmongen

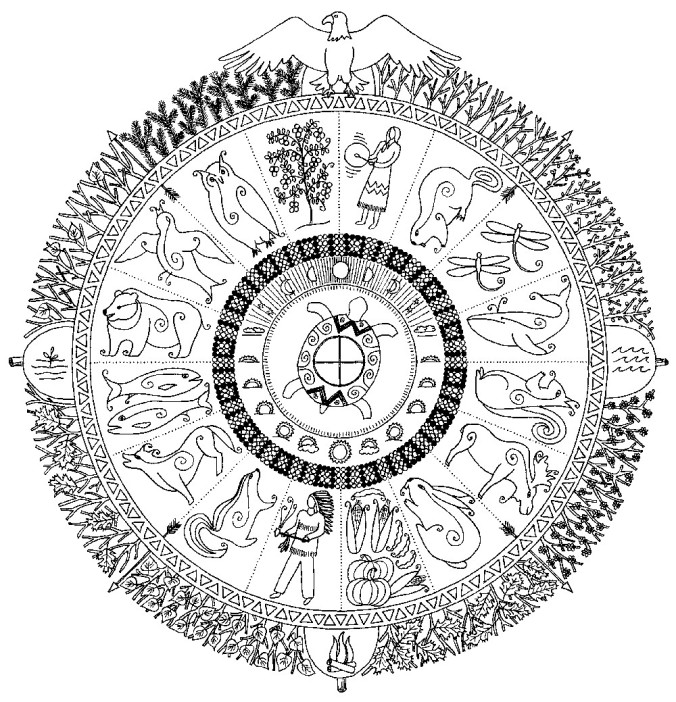

ITROFILLMONGUEN: Set of tangible and intangible elements central to Mapuche life, including spiritual energies or newen and the che or human person as indissoluble parts of the diversity of life that makes up each space or Lof that we inhabit.

For us as Mapuche, all the elements of nature are vital. In our worldview, everything is alive: soils, lakes, oceans, rivers, water springs, forests, wetlands, flora, and fauna, and together they allow us to live in balance and fullness. The balance of each of these elements on earth is intrinsically linked to the health and integral development of the Mapuche in the earthly and spiritual aspects. The survival of future generations depends on continuing to recreate and safeguard livelihoods coexisting with our natural environment; what we conceive of as Good-living or Kvmemongueleal. This will allow us to contribute to mitigating climate change while adapting resiliently.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- Read more about the Mapuche Environmental Association Budi Anumka

- Approaches to conservation by the Lake Budi communities

- Watch a short video about Budi Anumka’s work

Tshinanu

We know that it is possible to learn a language using a dictionary, a grammar or by taking a course. As we dedicate more time, we learn words, a basic vocabulary and sufficient pronunciation to enable us to understand and speak. We all learned the mother tongue of our family when we were toddlers, but only very few of us looked for the meaning of this language, and of its importance in influencing our lives. To undertake this search is to embark on an exceptional journey which can transform our entire life. This is a journey I have lived in investigating the words of my own language, Nehluen.

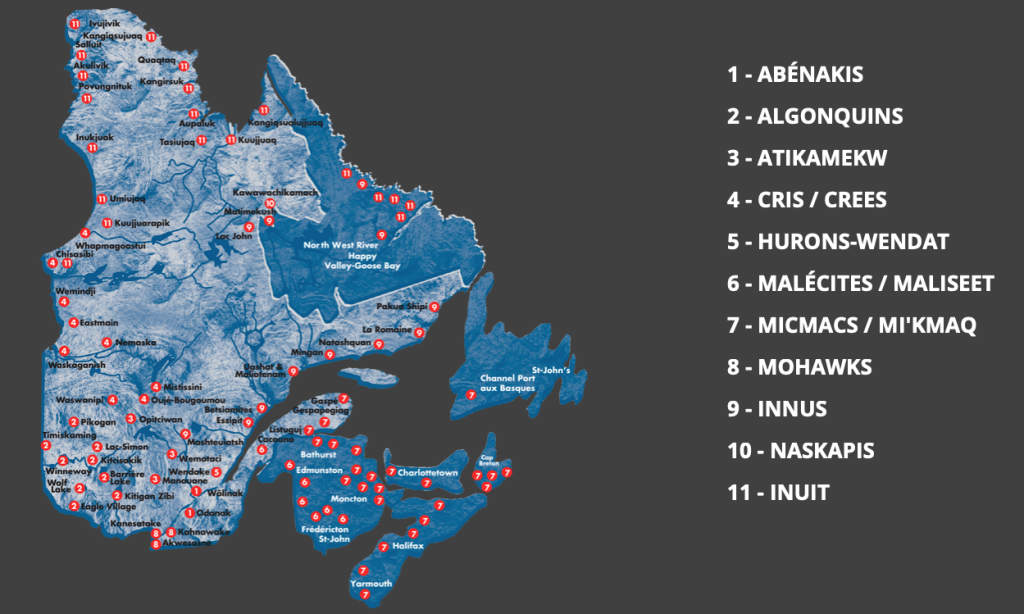

This is the common language used throughout the Innu communities in the province of Quebec, Canada, from Lac St-Jean to Labrador, passing by the lower Côte Nord. The Innu alphabet is based on 11 consonants and 7 vowels. It is indeed a complex language to learn by a new student, but so rewarding because it is so pictorial. The words represent more than a simple concept; they create a picture, a scene, animate a thought, define a precise action linking it with the environment. The Innu words are very exact, descriptive, and full of life.

The underlying reason is that there is one vocabulary adapted for village life and another one for the bush. These nuances are linked with the corresponding environment, which itself is indissociable from thought, and therefore the verbal expression. Since the landscape changes as we move from the South to the North, and from the East to the West, we also see it is reflected in the words used to designate the specific features of each place. It is in fact this precision of the words that enables us to understand the relationships which exist between the flora, fauna and the animals who live there. The human being must adapt to the decor, as he is a part of it. He is included in this big circle where interdependence prevails.

To better understand the base of the Innu language, we have to position ourselves in the context of circular thought. A human being and his environment are indissociable in this kind of thought. The pronoun ‘we’ will serve as an example to better understand the possible shades. If I wanted to speak of ‘we’ which includes me and you (singular or plural), then I would use ‘TSHINANU’. The prefix ‘TSHI-‘ corresponds to you in all its forms. If I wanted to speak about ‘we’ but in a way which is excluding you, whether singular or plural, I would say ‘NINAN’ (with the accent on the second N). Tshinanu – the inclusive form of we – invites sharing, community life, as there are no fences in the word tshinanu. It is a collective ‘we’, an open hand extended to others, inviting them to be a part of the circle. It also correspondingly tells a story, the story of the community of life of the person who speaks or writes. This word brings into relation the land, the animals, the plants and the peoples in the same pronoun.

The exclusive ‘we’ (NINAN) represents the person who is speaking about something, but without the listener or the group of listeners. Take, for example, a hunter who speaks about the moment when he was alone with the deer. He’ll say NINAN because, of course, the listeners weren’t there with him at that exact moment with the deer. The precision of the word thus conveys a very clear picture of the message, defining the role of everyone in the described scene. Speaking a language is a lot more than using words, as it also defines identity and belonging. It draws a portrait of the person’s native origin.

To speak of the area in Quebec inhabited by the Innu peoples, we use the word Nitassinan (our land), which also speaks to our inside land, our roots. For the traditional land of our families in the bush we say Nutshimit. It represents the land of silence, the inside discourse, the place of personal discovery, without any pressure. When presenting oneself and giving the name of the person’s community, people have an idea of the individual through the territory, which in turn speaks of a particular culture and way of life of the people living there, whether nomadic or sedentary.

When an Innu person is cut off from his/her territory, it deeply severs the bond to his/her identity. It means a loss of living roots, like becoming a stranger to him or herself. As a result, the words, loaded with context, lose their bearings in the new environment, there is no more silence, there are no roots. It is exactly this kind of broken bond, this deep wound that best describes placing indigenous peoples in reserves and residential schools, and healing will only be found by a return to the tradition. Let’s remember that the survival of our nations following these traumatic events rests on the shoulders of our elders who proudly protected our culture through the oral tradition. Our environment is the land, the forest, the plants, the insects, the animals, the water, the air and the human beings who are the stewards of the creator’s gift. An interdependent circle of life. From generation to generation, our teachings say that the earth doesn’t belong to us, but rather we belong to her, bearing in her our own distinctive roots.

Tshinashkumitin Iame

Missinak Kameltoutasset

A community celebration in Mashteuiatsh, Quebec in 2018

Marie-Emilie leads the ‘blanket exercise’ to engage people with the experiences of First Nations people.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- Learn more about the Innu people from the Canadian Encyclopedia

Chalay

The practice of chalay (or chhalay) embodies the Andean concept and value of reciprocity. It represents an ancestral alternative economic system which values, people, land and the sacred nature of food. Reciprocity is found at the heart of all relations, such that there are exchanges between people and mother earth, the apus (sacred mountains), plants and animals.

Historically in the Andes, non-monetary exchange has been linked to the ideals of economic and ecological complementarity, and contributed to self-sufficiency, not to economic gain. Although Andean farmers are now integrated into modern monetary economic relations, chalay continues to provide access to important goods and services without money. The farmers who practice chalay exchange foods, calculating the value of the products. In this case, value is not equivalent to the monetary value; rather it considers the time and effort for production, transportation, and takes into account the social relations between those doing the bartering, and the needs of the participants. The exchanges strengthen the relationships between family members and friends from different agricultural zones. Foods and seeds are also members of the family. When seeds are exchanged, the new seeds become ‘daughter-in-laws’. These new family members need to be treated with great care and respect so they will produce well.

I make chalay with corn seed. For the paracay variety, I make chalay with other women from the Rosaspata community. For seeds of the qello uwina variety I make chalay with women from the Ccachin communities. When I do chalay and exchange information on how to raise the seeds, we adopt them into our family, this helps the seeds from other places to adapt well to the land of my community, so we get a good harvest of corn.

Basilia Quispe Fernández

People who live in the middle zone, where there is maize, wheat and beans and there is little potato production, desire the delicious potato from the higher zones, as well as chuño and moraya (two kinds of freeze-dried potato). Those from the high zones desire the rich diversity of maize from the middle zone. From these two zones, they can also exchange for aromatic plants, fruits and vegetables from the valley. In this way, the families of the three zones exchange their products to diversify and balance their daily diet, and improve the nutrition of their children.

Chalay respects the sacred nature of food. Maize and potato are the source of life. They are for food, to sell, to trade for other products, to work in the fields. When taking the seeds to the market or another place, they smoke them in ritual, calling on Pachamama, asking her not to take the spirit of the plants, asking for them to remain in the community. When bringing new seeds into the home, offerings of coca leaves are made and they are sprinkled with chicha to welcome the seeds to their new home. Exchange in chalay is seen as an important part of the life journeys of the seeds.

Our Apu, sacred mountain, is the snow-capped Ccolque Cruz, with whom we do chalay in the month of August, which is carnival for our animals, for the cow, alpaca, llama. We make an offering to the Apu as a chalay, to help take care of our animals, so that they do not get sick. These times a disease has appeared that is killing our animals. Before we had more animals in this sector of Mapaccocha, many alpacas, llama sheep, and wild species such as llullucha (edible bacteria), now there is little llullucha and fewer animals.

Saida Juares Mamani from the Mapaccocha sector

In the barter markets (Chalayplaza), people used to bring many different products, including dry alpaca meat, wool, leather, and ceramic or iron products, but the conditions are changing. Some products, like salt or sugar, are almost fully integrated into the monetary economy. Some resellers of food products participate in the barter markets and try to exploit or trick the farmers. In these cases, the exchange is no longer respectful or just.

ANDES and the indigenous communities of Lares recognize the importance of chalay, and are researching the evolution of the chalayplaza over the past 20 years. During the research, local community members expressed an interest in protecting and promoting the practice of chalay. In June 2021, a municipal ordinance was approved to recognize the importance of the barter markets:

“Declare the practice of ‘Chalay’ or Traditional Exchange of Crops and Seeds, which takes place in the market places of Hinopampa, C.C. Choquecancha, C.C. Q’achin and C.C. Huacahuasi, as an Expresion of the Immaterial Cultural Heritage of the District of Lares, which contributes to the conservation of agrobiodiversity and food security of the local population” .

Ordenanza Municipal No004-2021-MDL, Lares, 15 de junio del 2021

Another reflection of the interest in protecting the barter markets is a new collaboration between two Biocultural Heritage Territories, The Potato Park in Pisaq and The Chalakuy Maize Park in Lares. Members of the two parks, together with Asociacion ANDES, are working to preserve ancestral knowledge and practices related to the Andean landscape and food systems, including chalay.

I do chalay in the Choquecancha market, we’ve always done chalay here. I have been doing chalay since I was young. Chalay is very important to exchange food products, to balance our diet, you don’t use money and that helps my budget. I am very happy because now more people are coming to barter. Like the communities of the Potato Park, I want the chalay to be more frequent.

Simeona Huillca Betancurt

Full list of contributors

Asociacion ANDES

Tammy Stenner

Parque de la Papa

Jhon Ccoyo Ccana

Ricardina Pacco Ccapa

Aniceto Ccoyo Ccoyo

Nazario Quispe Amao

Lino Mamani Huarka

Mariano Sutta Apocusi

Ciprian Ccoyo Banda

Bacilides Jancco Palomino

Daniel Pacco Condori

Parque Chalakuy

Ricardo Pacco Chipa

Juan Víctor Oblitas Chasin

Alberto Condi Durian

Saida Juares Mamani

Alfredo Hancco Santacruz

Maritza Churata Ttito

Basilia Quispe Fernández

Simeona Huillca Betancurt

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

Aibidil

Our understanding of the world is shaped by the language we use to describe it.

Aibidil is the Scottish Gaelic word for ‘Alphabet’. The Gaelic Aibidil has 18 letters and each letter is represented by a tree. The oldest living thing in Western Europe is a 2,000 years old Scottish Yew tree in Fortingall.

Gaelic is one of the oldest languages spoken in Europe today. It is more than a thousand years older than English and still spoken in Scotland and Ireland.

This ancient affinity between the Gaelic word and the tree embeds a deep association between language and landscape in the original roots of Gaelic. It gives an ecological substance to the alphabet – the foundation of all literacy – a language we can learn by looking at the landscape.

The Aibidil appears in numerous historic contexts from illuminated Celtic manuscripts to Dwelly’s seminal illustrated Gaelic Dictionary.

It continues to inspire 21st Century artists such as Alasdair Gray, Donald Urquhart and Jon Macleod.

Irish artist Katie Holten’s long-term research into Ogham runic script has led her to develop a coherent, beautiful and downloadable Tree Font.

Forester, Boyd Mackenzie, has spent 30 years planting and nurturing all of the trees of the Aibidil on his Hebridean croft. He has created a living conceptual artwork – an alphabet we can walk through.

Credits

- Malcolm Maclean – Director

- Ged Yeates – Editor

- Richard Davis – Aerial film

- Sam Maynard – Camera

- Flora MacNeil – Music – Craobh Nan Ubhal (The Apple Tree)

- Anna Mackenzie – Voice

- Ria Maclean – Voice

- Eve Maclean – Voice

Featured artists:

- Katie Holten (article describing Katie’s work with the tree alphabet)

- Alasdair Gray

- Donald Urquhart

- Jon Macleod

- Boyd Mackenzie

Thanks to:

- Prof Murdo MacDonald

- Mairi NicGilliosa

- Padraigin Ni Uallachan

- Maighread Stiùbhart

- Ruaraidh MacIlleathain

- Alasdair Maccallum

- Dr Finlay Macleod

- Prof Frank Rennie

- Bernard Loughrey

- John Dyer

- Marianne Campbell

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- Book of Kells

- Dwelly’s dictionary and the ‘Digital Dwelly’

- Prof Murdo Macdonald’s articles “Alphabet, Colour, Gaidhealtachd: An Ecology of Mind”; “Art, Maps and Books: Visualising and Re-visualising the Highlands” and “Five Essays into Highland Space”

- Ruaridh MacIlleathain: Ecosystem Services and Gaelic: a Scoping Exercise for Nature Scotland (2021)

Tamposati

The meaning of Tamposati, in English

My father says that Tamposati means that we are those born in the Tambo River, guardians and caretakers of our nature. For me, Tamposati is my home, I lived my childhood there, I had the joy of enjoying everything that nature provides.

Since I was a child, my parents taught me to sing. Today I reaffirm my cultural identity as an Asháninka woman singer and I make myself visible through my cultural expressions such as my clothing, my customs and my language, raising up our culture.

Detaching myself from my community was difficult. For this reason, every time I return, I try to attract tourists by doing free events to help us spread our customs. When I am within my community, I help with chores like cooking food from our fields such as yucca and cacao, fish from the river and many others.

Our culture is alive and so is our technique. I am proud to carry this legacy with me and to be able to share the beauty of our culture with the world. Preserving our language is important for future generations to enjoy our cultural richness.

El significado de Tamposati en español

Cuenta mi padre que Tamposati significa que somos los nacidos en el Río Tambo, guardianes y cuidadores de nuestra naturaleza. Para mí, Tamposati es mi casa, viví mi infancia ahí, tuve la dicha de disfrutar todo lo que la naturaleza provee.

Desde niña mis padres me enseñaron a cantar, de esa forma hoy yo reafirmo mi identidad cultural como mujer cantante Asháninka y me hago visible a través de mis expresiones culturales como son mi vestimenta, mis costumbres y mi lengua, dejando en alto el nombre de nuestra cultura.

Despegarme de mi comunidad fue difícil. Por eso, cuando regreso me preocupo por intentar atraer turistas que nos ayuden a difundir nuestras costumbres haciendo eventos gratuitos. Cuando estoy dentro de mi comunidad ayudo en los que haceres como cocinar los alimentos de las chacras como la yuca y el cacao, del río los pescados y muchas otras más.

Nuestra cultura se mantiene viva y nuestra técnica también. Estoy orgullosa de llevar conmigo este legado y poder compartir con el mundo la belleza de nuestra cultura. Conservar nuestra lengua es importante para que las siguientes generaciones gocen de nuestra riqueza cultural.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- Find Yessica Sánchez on Facebook

- Watch videos of Yessica’s singing on her YouTube channel and in the concert ‘Cholos Somos’

- CHIRAPAQ, Centre for Indigenous Cultures of Peru

Kyká

The poem of Kyká, by Nicolás Acosta

The myth is recreated in the everyday, in the day to day, giving meaning to existence while walking.

Our people once again raise their houses, raise their spirits, their voices. In the infinite gaze that meets the glow of the sky at dusk and becomes breath the next morning. When the sun struggles to penetrate the multiform droplets of fog and smoke crawling through the straw of our ceremonial houses.

To be the hope of a people that walks the roads in daily activity, surprise filling every step in the amazement of another life that crosses the road, showing its colours of flight.

And in the cold kiss of the mother, it finds the cascade of illusion in the memory of the Grandmother, who greets and is recognised in the transcendence of her toothless smile.

It is our story that is also a song, raised in the humidity that shelters in the leaf litter that caresses the earth with its thick hands, but does not impede the sensitivity of the caress, the solidarity in the embrace.

The good thought and flirtatious smile that hides the food for the mother to multiply it in her life-creating action.

The territory feeds on hopes for the future. It asks for medicine to heal the people, the lake asks for water to bring babies, the stone asks for strength in thought. The river that flows with the freshness of life. Possums, foxes, rabbits, weasels, crabs and armadillos protect their existence in the underground that provides the raque tree, the myrtle, the hayuelo, the fern, the arboloco, and the frailejón plants.

While the prayer wakes the guard with all the grandparents and grandmothers, siblings, who in their resting place, feed their bones with the glow of the stars, radiating the feeling of our footprint on the hill.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- #soscerroseco: an active campaign to halt mineral extraction on sacred territory outside Bogotá. Search for this hashtag on Facebook.

- COLECTIVO DE EDUCACIÓN PROPIA PEDAGOGÍAS ANCESTRALES

- CONA – Pedagogías Ancestrales on Facebook

- Fundación Zaquenzipa: Wellbeing from ancestral thought (includes Spanish-Muisca dictionary)

Scrogs

Stories are living beings, they grow, they develop, they remember, they change not in their essence, but sometimes in their dress. They are shared and shaped by the land and the culture and the teller…

Robin Wall Kimmerer

Robin Wall Kimmerer in ‘A Note on Indigenous Stories’ in her book, Braiding Sweetgrass, makes a cogent point about her people, originally from the Great Lakes. However it is equally pertinent to the oral culture of Scots travellers.

Here I will, with digressions, focus on a particular ballad sung within a family of settled travellers, some of whom I knew well when I was younger. The ballad, Johnnie the Brine was learned from a recording made by my colleague, the late Peter Hall. There are versions spread across Scotland and into England but only the Robertsons identify the protagonist as Johnnie the Brine. It displays characteristics of many songs beloved by travellers – transgressive, out with societal norms and reflective of older ways that are no longer conducive to a ‘modern’ lifestyle.

Listen to Arthur Watson singing the ballad of Johnnie the Brine

Creating the story of |Xau

Read the full post about the word |Xau

Selection of artist works from the film of |Xau

Virginia MacKenny

(r) ‘Woodrose Explosion’ 2020 watercolour 29.5 x 23 cm.

Images copyright V. MacKenny

Ndaya Ilunga

Images copyright Ndaya Ilunga

Margaret Courtney-Clarke

(top right) The Ostrich Egg, Omaheke Region, Namibia, March 2019

(bottom) The Rain Dance #2, Omaheke Region, Namibia, October 2019

All images copyright Margaret Courtney-Clarke from her book ‘When Tears Don’t Matter’

Contributors to the film

- Prof Sylvia Vollenhoven – Script, Concept & Editing

- Ryan Lee Seddon – Cinematographer

- Kutelani Rasikhuthuma – Online Editor

- Prof Virginia MacKenny – Concept and Main Artworks: Of Holes and Things, Woodrose Explosion and Sharp Edged Grains

- Ndaya Ilunga – Word and Graphic Art: It’s Only Words and Playing with Empty Words

- Margaret Courtney-Clarke – Photographs from When Tears Don’t Matter and Archive Footage: Fire Dance

- Hilton Schilder – Music: Kalahari Thirst, Alter Native and eMail to the Ancestors

- Basil Appollis – Voiceover artist

- Bradley van Sitters, aka Danab ||Hui !Gaeb di !Huni!nâ !Gûkhoeb – Khoekhoegowab voiceover artist