ITROFILLMONGUEN: Set of tangible and intangible elements central to Mapuche life, including spiritual energies or newen and the che or human person as indissoluble parts of the diversity of life that makes up each space or Lof that we inhabit.

For us as Mapuche, all the elements of nature are vital. In our worldview, everything is alive: soils, lakes, oceans, rivers, water springs, forests, wetlands, flora, and fauna, and together they allow us to live in balance and fullness. The balance of each of these elements on earth is intrinsically linked to the health and integral development of the Mapuche in the earthly and spiritual aspects. The survival of future generations depends on continuing to recreate and safeguard livelihoods coexisting with our natural environment; what we conceive of as Good-living or Kvmemongueleal. This will allow us to contribute to mitigating climate change while adapting resiliently.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- Read more about the Mapuche Environmental Association Budi Anumka

- Approaches to conservation by the Lake Budi communities

- Watch a short video about Budi Anumka’s work

Kyká

The poem of Kyká, by Nicolás Acosta

The myth is recreated in the everyday, in the day to day, giving meaning to existence while walking.

Our people once again raise their houses, raise their spirits, their voices. In the infinite gaze that meets the glow of the sky at dusk and becomes breath the next morning. When the sun struggles to penetrate the multiform droplets of fog and smoke crawling through the straw of our ceremonial houses.

To be the hope of a people that walks the roads in daily activity, surprise filling every step in the amazement of another life that crosses the road, showing its colours of flight.

And in the cold kiss of the mother, it finds the cascade of illusion in the memory of the Grandmother, who greets and is recognised in the transcendence of her toothless smile.

It is our story that is also a song, raised in the humidity that shelters in the leaf litter that caresses the earth with its thick hands, but does not impede the sensitivity of the caress, the solidarity in the embrace.

The good thought and flirtatious smile that hides the food for the mother to multiply it in her life-creating action.

The territory feeds on hopes for the future. It asks for medicine to heal the people, the lake asks for water to bring babies, the stone asks for strength in thought. The river that flows with the freshness of life. Possums, foxes, rabbits, weasels, crabs and armadillos protect their existence in the underground that provides the raque tree, the myrtle, the hayuelo, the fern, the arboloco, and the frailejón plants.

While the prayer wakes the guard with all the grandparents and grandmothers, siblings, who in their resting place, feed their bones with the glow of the stars, radiating the feeling of our footprint on the hill.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- #soscerroseco: an active campaign to halt mineral extraction on sacred territory outside Bogotá. Search for this hashtag on Facebook.

- COLECTIVO DE EDUCACIÓN PROPIA PEDAGOGÍAS ANCESTRALES

- CONA – Pedagogías Ancestrales on Facebook

- Fundación Zaquenzipa: Wellbeing from ancestral thought (includes Spanish-Muisca dictionary)

Siwa

From the waters emerged Mother Bachué, who gave birth to our people and taught us how to live well in our territory.

When father and mother created the world they wondered – who will take care of the world and teach to maintain order?

It was thus that they sang a new song and placed two new seeds in the womb of humanity, the lake from which Bachué and the primeval law of caring for creation emerged.

The lake is that portal from which possible worlds are born and where the spirit of struggle and natural order is strengthened. Our waters are creative centers, navels and connection paths that allow us to dialogue with other ways of thought.

Its waters sing stories, siwa speaks to us and reminds us of the womb, of the humidity of our first ‘mochila’ (cotton shoulder bag), our mother’s womb.

Returning to the lake is to reimagine ourselves, to look at ourselves in the mirror of its waters and recognize ourselves to organise our thoughts and spirit.

We are sons and daughters of the lake, our bodymind is nourished from its waters. It is a call to listen to the mother’s voice, to fertilize the thought that sows and sustains resistance

To organize ourselves around water as knowing and not as a raw material, it is vital to stand firmly before the capitalist thought that turns the lakes into resources, and to resist in the face of its absurd approach to land use that overflows and destroys the territory, blurring from our hearts the firm idea and conviction that the lake has life, spirit and purpose.

In your waters I was born, with them I found myself and I will take care of your flow to sow myself and be a daughter. I will walk so that you continue living, because in you the rhythm of the universe is manifested, because in you the balance is maintained and I am made of you. We will sing so that your pain heals, so that life is reborn again and the will of the peoples continues to be born to return to their law of origin.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- COLECTIVO DE EDUCACIÓN PROPIA PEDAGOGÍAS ANCESTRALES

- CONA – Pedagogías Ancestrales on Facebook

- Fundación Zaquenzipa: wellbeing from ancestral thought (includes Spanish-Muisca dictionary)

Creating the story of |Xau

Read the full post about the word |Xau

Selection of artist works from the film of |Xau

Virginia MacKenny

(r) ‘Woodrose Explosion’ 2020 watercolour 29.5 x 23 cm.

Images copyright V. MacKenny

Ndaya Ilunga

Images copyright Ndaya Ilunga

Margaret Courtney-Clarke

(top right) The Ostrich Egg, Omaheke Region, Namibia, March 2019

(bottom) The Rain Dance #2, Omaheke Region, Namibia, October 2019

All images copyright Margaret Courtney-Clarke from her book ‘When Tears Don’t Matter’

Contributors to the film

- Prof Sylvia Vollenhoven – Script, Concept & Editing

- Ryan Lee Seddon – Cinematographer

- Kutelani Rasikhuthuma – Online Editor

- Prof Virginia MacKenny – Concept and Main Artworks: Of Holes and Things, Woodrose Explosion and Sharp Edged Grains

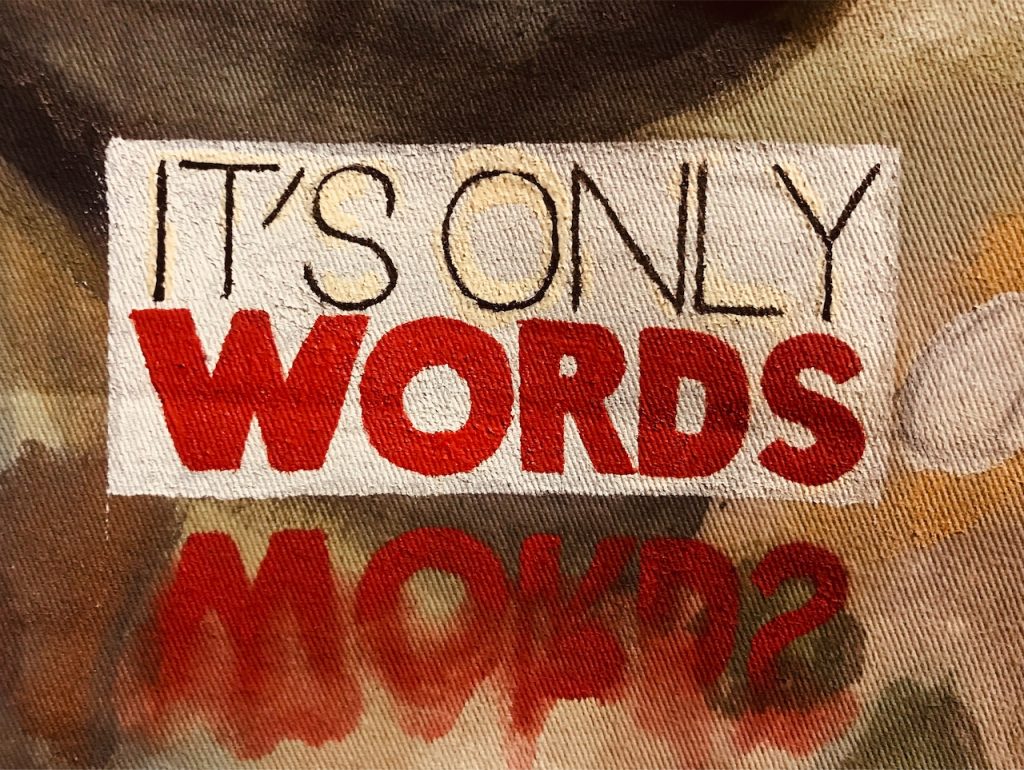

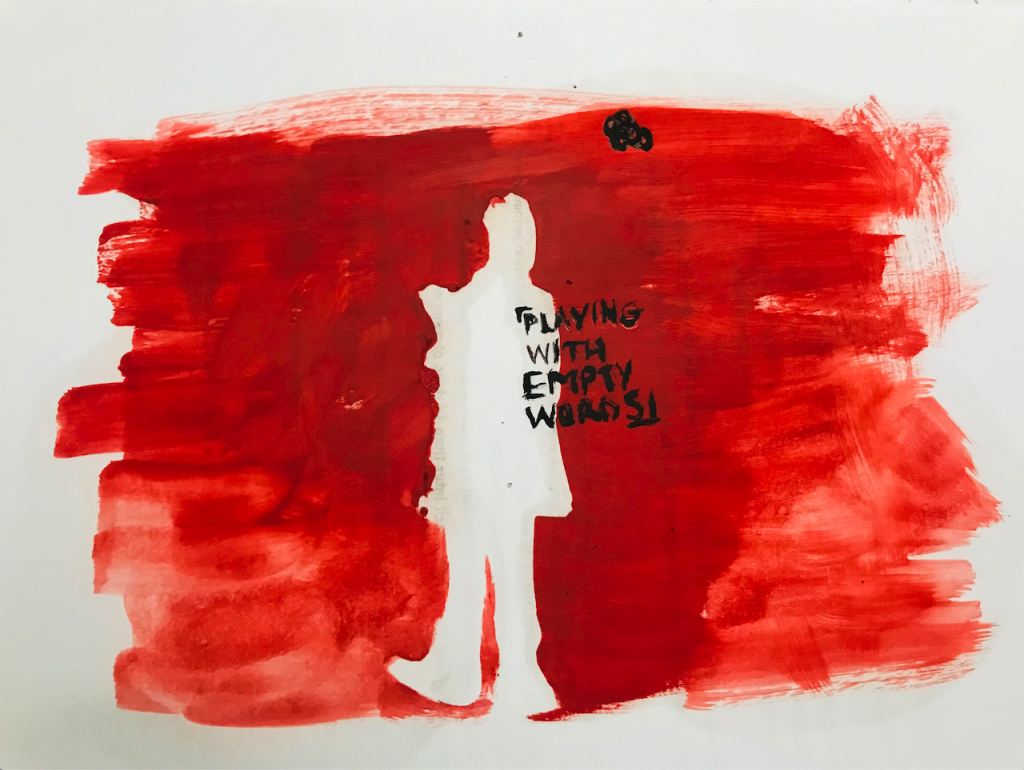

- Ndaya Ilunga – Word and Graphic Art: It’s Only Words and Playing with Empty Words

- Margaret Courtney-Clarke – Photographs from When Tears Don’t Matter and Archive Footage: Fire Dance

- Hilton Schilder – Music: Kalahari Thirst, Alter Native and eMail to the Ancestors

- Basil Appollis – Voiceover artist

- Bradley van Sitters, aka Danab ||Hui !Gaeb di !Huni!nâ !Gûkhoeb – Khoekhoegowab voiceover artist

|Xau

In the now extinct language of the |Xam Bushman people of Southern Africa |Xau or |Xaun meant to shoot with a magical arrow or go on a magical expedition.

My people had a word – No, more than a word – |Xau flowed through us – Lived in us – Connected us – Then it left us

When it went away – This word that is more than a word – It tumbled down the mountains – And out of our mouths – A precious possession… stolen, gone

Nothing has come to fill the vacant house of the |Xau – Magic does not live in the home of the new words – Disconnected broken arrows – Going nowhere

Our children play with empty words – That do not speak of mystical journeys

|Xau – My people had a word

|Xau – So much more than a word

|Xau – Melodies no longer heard

But deep in the earth there is healing – The land awaits our right doing – Ancestral Voices guide us back – To other Magical Arrows – And the melody of words that are more than words

To the |Xau of now

By Sylvia Vollenhoven

It is hard to restore our connections with the land, our love and respect of all that is, without finding the |Xau of now.

When I am a young girl growing up in apartheid South Africa my mother tongue is Afrikaans, a fascinating hybrid language with slave ancestry and the youngest on our Continent. It scoops up Asia, Africa and Europe in its arms and is closer to our hearts than English (the lingua franca of South Africa). When I am a young woman grappling with issues of identity, apartheid propaganda declares a version of my mother tongue to be the linguistic glue for driving the white Afrikaner people from racist nationalism to 20th Century nationhood.

For the mixed descendants of the colonials and the slaves (brought to South Africa mainly from Asia and other parts of Africa) our version of Afrikaans has been until recently the only tool we have had to build and solidify an African identity.

But now things are changing. We are going back into history to fetch precious intangible possessions that have been ripped out of our existence, out of our beings. There is talk of colonial overlords historically knocking out the front teeth of my people so that we could not pronounce the clicks of our indigenous languages. But in Southern Africa people are healing and relearning the languages that have survived, mainly Khoekhoegowab or its closest equivalent Nama.

The word concept |Xau, unearthed in an ancient dictionary, is a powerful example of what we have lost. The newer languages, inept by comparison, that have come to replace the rich indigenous lexicons do not have a word that comes close in meaning to “shoot with a magical arrow”.

When our languages were destroyed, we lost important elements of our culture and we lost entire civilisations. We have lost perspectives and a way of being in the world. Emulating a colonial way of expressing ourselves, our connection with the land and with the divine aspects of ourselves has been broken. This disconnect this brokenness, fuels self-destruction and in the process aids the destruction of the earth that sustains us.

Tumbling around in the maelstrom of the modern world, in search of what we have lost, we need to find those magical arrows. We need to find the |Xau of now to restore our relationship with the land and the divine within. Only then can we return to valuing the earth once more. Only then will we begin to heal what has been destroyed without and within.

Sylvia Vollenhoven is an indigenous South African author, playwright and filmmaker. Her seminal work on Khoesan identity, The Keeper of the Kumm, was awarded the nation‘s prestigious Mbokodo Prize for Literature and short-listed for all the major SA literary awards.

More about the |Xam language

The Language from which the word |Xau or |Xaun comes is |Xam (hear how to pronounce this word)

ǀXam is regarded by some as an extinct language of the Bushman people (a reclaimed and preferred term) of Southern Africa but its resonance can be found in modern Khoikhoi languages on the sub-Continent. The main, related modern language that has survived colonial devastation is Khoekhoegowab. |Xam was spoken by the ǀXam-ka ǃʼē people. This name or grouping was more a regional and geographic distinction than anything else. Much of the scholarly work on ǀXam was performed by Dr Wilhelm Bleek, a German linguist of the 19th century, his researcher sister-in-law Lucy Lloyd and their ǀXam-ka ǃʼē teacher informants ǁKábbo, Diaǃkwāin, ǀAǃkúṅta, ǃKwéite̥n ta ǁKēn, ǀHaṅǂkassʼō and other speakers. As a result, there is a surviving corpus of ǀXam that comes from the stories told by these individuals in the Bleek and Lloyd Collection at the University of Cape Town. Bleek’s daughter Dorothea added to the work, compiling a “Bushman Dictionary” that was published many years later.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

Wíyukčaŋ

This contribution is edited from a series of conversations with Tiokasin Ghosthorse, project producers, Neville Gabie and Philippa Bayley, and fellow contributor Malcolm Maclean.

Neville: As you have described it, Lakota is a language of verbs because everything in our world is alive, in motion, active. That idea completely changed my thinking because suddenly I could no longer see a tree as passive, but as actively being – ‘treeing’.

Tiokasin: If you see something in motion and suddenly it stops then you have to noun-ify it and it does not have any life – it does not have any motion… It becomes ‘a thing’. To think in the ‘earth paradigm’ (rather than in the ‘human paradigm’) – when you are seeing something in motion it is a more alive way to see and feel something because you are part of it. Your eyes are actually a part of that energy of motion, so you describe it that way. And then you describe the energy that you are feeling. So these two ways of understanding – motion and energy – are probably as close a way of getting to say how the language is structured.

The English language is not effective enough because we use concepts which are very basic building blocks. Concepts get in the way. Concepts put barriers in the mind and in the spirit too.

Neville: I remember you were saying that the human body and the trunk of a tree have the same word in Lakota – čaŋ. Can you say more?

Tiokasin: čaŋ is a tree – so we are talking about a torso, we are talking about the finger, the arm, and our hair is the leaves, you can go on, and our toes are the roots. It’s not just that your body is a tree – it’s the wíyukčaŋ – knowing, consciousness. You hear the čaŋ in it? So, in Lakota thinking, when you fragment the word: wí-yu-kčaŋ… Wí is the sun and to us, sun is a verb – it is being and it is always alive. And the yu is like the consciousness that is given to the tree and the tree is acknowledging the sun. This is not just us as the body of the tree, but this is the tree of who we are. We can spiral out into a bigger thought: Wow, the consciousness of the sun is the consciousness of the tree and vice versa. And we are the acknowledgement of it because look how we are made. We don’t have the language for that in English. I am speaking so many English words to describe one little thing!

Wíyukčaŋ – that’s knowing, consciousness – the wíyukčaŋ is also involving the moon and the stars and the trees of the earth and how they communicate, and we are in that as humans.

Philippa: You have talked about people becoming ‘technical human doings’ rather than ‘organic human beings’. Can you say more?

Tiokasin: In the older world, in the petroglyphs and hieroglyphs, you can see humans and nature; in some of the prophecies the Hopi have their feet below the ground as if they are planted. And the technical people are going nowhere, they are not planted. So that means their minds have become ethereal and disconnected. We are at a point now where there is still a chance for the majority to start thinking differently, more earth-oriented. There are a few who retain that sobriety with the earth. Otherwise we become intoxicated with our own humanness and get into the patterns of thinking we have superior intelligence, and that’s defined by concepts in the language.

It’s not progress to lose consciousness with the earth. Where is the language to keep that aliveness of the earth? You see how much confidence children have with the earth. They have a lot of confidence with the earth and then that’s torn down and replaced with false confidence. When my friends come from the more urbanized settings they are in nature and it’s all new and they are afraid of it, because they have no confidence in nature. So they will get their manuals out, so they can identify, but the butterfly is not thinking about identity.

When you are not confident with the earth, you lose your roots. But what I see is that as native people – we can wander but we know who we are. In the USA we are landless, we are landless as native people, but we are not homeless. Ok, temporarily we don’t have the land, but who said that we had it anyway? So those binding languages that are forcing you to say ‘you need to think this way – let’s make a treaty’ and yet history says ‘but where is your contract with the earth?’ That is our responsibility – being with the earth making sure that she is maintaining all life including the little human being.

Malcolm: That was a wonderful thing you said there about being landless, but not homeless. It applies in my part of the world as well. We have a famous poet here, Norman MacCaig, and I have to paraphrase it… ‘Who does this land belong to? The man who claims to possess it, or me who is possessed by it? ‘

Tiokasin: What if we thought in terms like that? You belong to the earth? And if you think like that then your language is confident. If you maintain a relationship with the earth, rather than control of the earth, that all life will be here. We started by saying ‘if we need the earth, does the earth need us?’ In a Western context we would say ‘of course we can save the earth; of course we can do this’ but that is an industrialized way of thinking and at the same time we are thinking she is going to flick us off like a flea. It’s not even a question. If the earth needs us because we are the earth it’s a sense of responsibility: ‘Yes, of course we need the earth, but of course the earth needs us.’ We are here in a relationship, so our language is all of relationship.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Hyká

The stones are the word, and the latent memory of our territory and of our ancestors. They are proof that they walked through these mountains. They are grandmothers who know a word, ancient, deep and complex; words of advice that can only be heard through patience, deep silence, and the other senses.

Rocky shelters that guard and make life possible, firmly hold our struggles and our thoughts. Their skin and their scars are witnesses to the passing of time, and in turn, they are living proof of our survival.

When we meet them, we sit down to look inwards, to our past stored there. We dream to remember the paths of the ravines and the song of the birds of yesterday. We ask about their purpose and teachings.

The hyká are bridges that have allowed us to remember and legitimize the struggle for the wellbeing of our people.

The hyká are our grandparents and we will defend them.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- #soscerroseco: an active campaign to halt mineral extraction on sacred territory outside Bogotá. Search for this hashtag on Facebook.

- COLECTIVO DE EDUCACIÓN PROPIA PEDAGOGÍAS ANCESTRALES

- CONA – Pedagogías Ancestrales on Facebook

- Fundación Zaquenzipa: wellbeing from ancestral thought (includes Spanish-Muisca dictionary)

Ïe cho

Ïe cho

Our ‘living well’ is Ïe cho (good path); it is being aware that we are all part of Mother Earth.

It is devoting our life as human beings to uniting with the territory we inhabit and in which we’ve been sown.

Ïe cho is taking care of the territory.

It is taking care of our relationship with birds, the wind, the earth, water, fire, trees, plants, stones, our ancestors and all the spirits that walk with us.

It is taking care of our family, our traditions, our memory. It is forgiving the past and making peace with it.

By living Ïe cho we realise that a development model that is against life has been imposed on us. Mining, dams and extraction of hydrocarbons destroy mountains and lakes and at the same time, peoples and their memory are destroyed as well.

In order to live in accordance with Mother Earth, she enables us to talk to and learn from medicines, food, the practice of weaving, offerings and the spirits of the territory, which also live in us.

Ïe cho is resisting in community, making our relations balanced in reciprocity and common-unity, and learning together from difficulties.

Walking Ïe cho is understanding that when we become earth again, out body returns to our mother.

We need to walk Ïe cho in order to understand it.

Have you said we, Indians, will not go to heaven because when we die our soul also dies, or goes to the Páramo and becomes a deer or a bear? [Question taken from the confessionary included in the anonymous manuscript N° 158 (17th Century) at the National Library of Colombia]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- COLECTIVO DE EDUCACIÓN PROPIA PEDAGOGÍAS ANCESTRALES

- CONA – Pedagogías Ancestrales on Facebook

- Fundación Zaquenzipa: wellbeing from ancestral thought (includes Spanish-Muisca dictionary)

Reflecting on the Sardaks

Paintings by Tsetan Angmo, Ladakh, India

Read the full post about the word sardak

ས་བདག or Sardak

Relearning to live with ghosts

Kayi, Kayi; Sardak na Doa-dak. “The owners of the land and the rocks, please accept our food”. Kayi is an odd and old pronunciation of the Urdu word Khao, meaning eat. Sardak is composed of two words, sa (land) and dakpo/mo owners of the rocks. Doa is rock.

The word sardak means much more than the English ‘owner of land’; The roots of the word, with their tentacles, meander and take us to the first person (the original sardak of a household) who established the first farm, which gave him/her the food. The farm that led to the formation of his/her household. The household members created the first romkhang; the place where the dead person’s body was burnt to convert it back to soil and rocks. The following generations also converted to dust in the same romkhang. Siblings parted ways and the number of households grew; new romkhangs were made. The new, however, must have a handful of the soil of the original romkhang. So all the people who found a place in the romkhang are dakpos; owners of the land (sardak).

Romkhang, is an odd word. It means the house (khang) of the dead body (ro). But the body is not just a body; it also is soil/land. Dust in any romkhang is a mixture of the bodies of the ancestors. I write this sitting in a house not far from our romkhang. The romkhang is located amidst stones, rocks and willow trees. In the high altitude, trees have to be cultivated for fuel and to build houses. These trees were planted by my grandfather, one of the later sardaks. His name was Tundup Paljor, who died in the 1980s, much before I arrived in human form. Paljor’s wife Tashi Chuskit and his two sisters, both named Zangmo co-worked to plant those trees. The soil in our romkhang also contains the body of my women ancestors. The grove of trees, a feature of the village landscape, owes their existence to them.

If I zoom out of the grove, I see terraced farms created and tree gardens planted by the sardaks of other households. The landscape from this vantage point had been indelibly marked by the presence of the sardaks. The farms, the trees, the old houses, the repaired monasteries, the crumbling stupas, the foot trails, the wooden bridges, the lhatos (the residences of benign spirits) and others were created by the sardaks. They and their livestock left trails. This landscape reminds me of our ancestors. They are absent but present, they are like ghosts. The ghosts of sardaks populate the landscape.

Zooming out further, we see that the T-shaped valley in which my village is located is surrounded by majestic mountains, formed 50 million years ago when two tectonic plates collided. In this landscape, the humans showed up much later. Yet the insignificant humans have marked significant marks on the landscape. The sardaks brought water via irrigation canals from the stream fed by the Shali Kangri glacier to their trees and farms. The ways of being of the sardaks enabled them to live here for thousands of years.

The landscape was constantly in the making. It still is. New houses built from imported cement, iron, wood, and paints are prevalent. Now, the three ends of the T-shaped valley are paved with motorable roads. All roads connect the village to the national highway and thereby to circuits of the global economy. The western side is fenced by the iron net to stop napos, a wild ungulate, from entering cultivated fields. Villagers opine that the lack of grass in wild pastures is the reason for their invasion, which in turn points to low snowfall in the winters. Metal fencing is supposed to be the defence against a changing climate. We are told that the glaciers in the Himalayas are melting quickly because of the settling of black soot on the ice sheets. One of the sources of soot are diesel engines. The imported cement and metals are implicated in the decreasing size of the glaciers. Two villages in Ladakh, Kumik and Kulum have had to be abandoned because their glaciers melted and springs dried up. Now, only ghosts live in these villages. The concrete houses, behemoth hotels, and metal fences are also haunted. The ghosts of past ways, with their human limitations, haunt these places. The ghosts are everywhere, if only we could learn to see.

Back to the romkhang, during Losar (Ladakh’s New Year) festivities, the living members of the household take food for the sardaks at romkhangs. It is during this time that in the Sham region of Ladakh these words are uttered: Kayi, kayi; sardak na doa-dak. Please accept our food. This practice is called sheme. Sheme is a reminder of the legacy of those who lived before us. I had never seen Tundup Paljor, but as a child, I took food for him and his other roommates.The modern encroachment of dualisms – of body/soil, life/death, subject (I)/object (landscape) – are destroying practices like sheme and blindfolding us to notice the connections and co-origination of everything. With the connections hidden, our landscape exists out-there to be gazed upon (by tourists) and to be tamed (by engineers and contractors) and so on. The real blind faith is to render the landscape dead. Opposed to bland, dead and feminised landscape, waiting to be tamed, sheme illuminates and enchants with magic, with ghosts. It invites us to relearn other ways of looking. It reveals the living history of our land via the ghosts of the ancestors, the sardaks.

This piece of writing was inspired by the work of Donna Haraway, Tim Ingold, Anna Tsing and native scholars.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.