‘There are no voices from this frozen continent. There are no people to speak for here, to break the silence. But the stillness above does not tell of the turmoil below. Who speaks for this place? Who will hear, who will listen, as ice tears itself apart?’

In 2008/09 I spent four months travelling in Antarctica as artist-in-residence with the British Antarctic Survey. Halley is the most southern British base accessible by ship through the Weddell Sea. It is the base which first detected the hole in the Ozone Layer and it continues to measure atmosphere, weather patterns and the shifting ice flows.

What that does not tell you is the amazing impact Antarctica has, or at least had, on me. It sounds like a cliché but I found the experience to be deeply profound and almost impossible to respond to creatively. Everything I tried seemed crass, lightweight in comparison to the vastness of a continent. A continent entirely without an indigenous community, just some temporary residents, mostly scientists trying to grapple with its complexities.

Unpopulated, this frozen, fragile continent is one of the fundamental building blocks of life on earth. It is meeting the importance of that directly and understanding the smallness of human life by comparison, that left such an impression. Yet it remains so vulnerable to human activity in other parts of the world.

Within a year of my return I had also spent time in Southern Greenland where there is an indigenous community. What stares you in the face immediately is just how quickly our landscapes are failing. Ice no longer freezes in the fjords, glaciers are rapidly retreating and a population which sustained itself for thousands of years can no longer survive without imports of food.

This work (text and photographs) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- The British Antarctic Survey: Polar science for planet Earth

- The Halley Station webcam

- More about Neville’s Antarctic residency

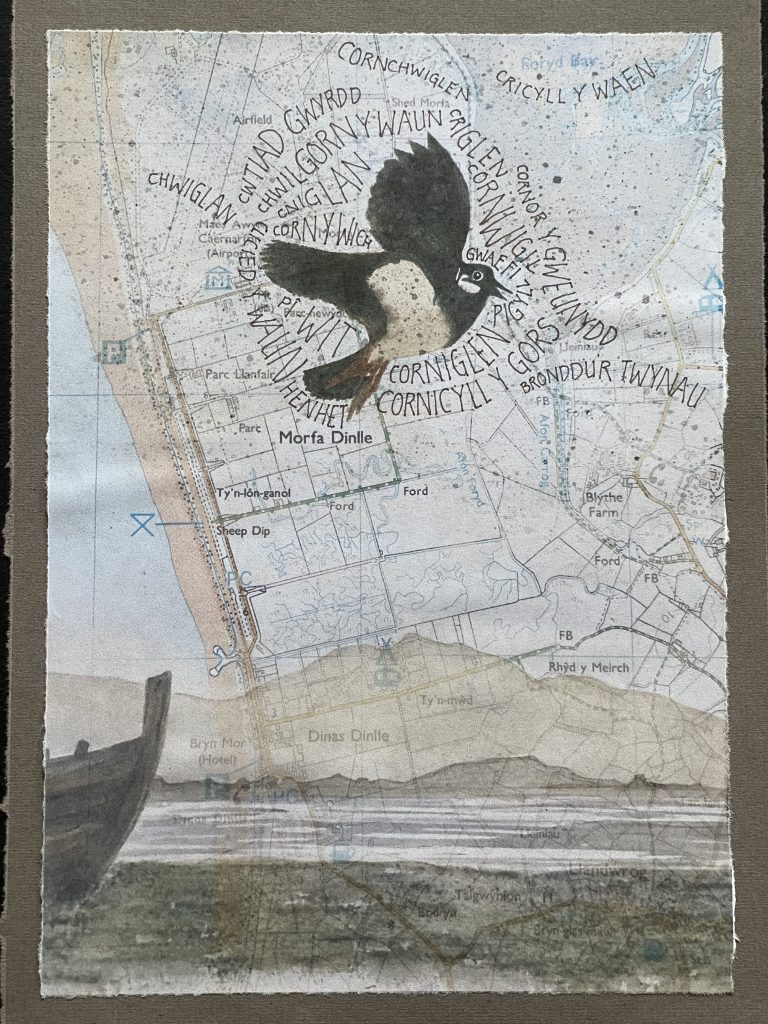

Gwae fi – lost names of the lapwing

Bricolage depicting local names of the lapwing, by Elinor Gwynn, North Wales, UK

Read the full post about the word Morfa

Elinor says: The number of different Welsh dialect names for lapwings is a reflection of how common the bird used to be. Collectively this set of names describe perfectly not only the distinctive features of the bird – the soft, feathered ‘horn’ curling at the back of its head and the lapwing’s unique repertoire of clicking, gurgling and whistling calls – but also the range of typical lapwing habitats. However, as lapwing numbers have dwindled, and as people’s everyday encounters with these birds have become less frequent, the local dialect names have also fallen out of use.

As I watched the lapwings wheeling and tumbling above Morfa Dinlle last spring I tried to recall as many as I could of these local names. They ended up spinning in my head, almost as if they were caught up in the vortex of feathered flight paths that filled the skyscape. I was struck by the entangled storylines of species decline and loss of language diversity; with one mirroring the other, and both resulting in blander landscapes and more impoverished lives. One of the lost local lapwing names – ‘Gwae fi’ [Woe is me] seemed to sum up perfectly my thoughts on that April morning.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Poem: The Marks t’ Gan By

Coble

The word ‘coble’ refers to the wooden boat traditionally used for inshore fishing on the NE English coast between Berwick-upon-Tweed in Northumberland and the Humber in Yorkshire. We offer the word because a coble is more than just a boat. Built by the eye, without a plan, its lines evolved over centuries for sail, to respond economically to the wind and local sea conditions. Its characteristic shape, deep ‘forefoot’ and flat bottom aft, developed in response to the need to launch from beaches.

Each coble brought human lives into direct, daily contact with powerful, unpredictable forces of nature. Fishing was seasonal, dependent upon what was locally abundant. Although the coble’s development is linked to estuarine salmon netting, at sea its prime winter catch was cod and haddock, caught using ‘long lines’, each carrying 700 hooks. In Northumberland, each man took two lines to sea.

As the focus of a family-based economy, a coble embodied the traditions, beliefs and values of concentric human circles: its crew of three men, their families, the village, and the culture of the entire coast. It required many skills – boat-builder, joiner, blacksmith, sail-maker or engineer – and supported local businesses selling paint, linseed oil, paraffin and ‘perrins’ of thread. In short, a coble represented a whole community.

Our submission comes from a small part of that community, a few Northumbrian families and the poet whose work they inspired. Their language, a distinctive dialect within Northumbrian, has nearly died out. Although there is a definite cultural continuity along what has been called the ‘coble coast’, there remain strong distinctions between ‘Northumbrian’ coastal speech (more Anglo Saxon), and ‘Yorkshire’ (with more Norse words). There are differences, too, between Northumbrian and Yorkshire cobles, and in the way the word is pronounced. It is ‘Cobble’ in Yorkshire.

The root of the word ‘coble’ is probably Celtic, but the boat’s geographical distribution ties it closely to Anglo Saxon Northumbria. The boat itself appears to contain elements from several strata of settlement: Norse, Anglo Saxon, Celtic. It is striking that such a distinctively ‘English’ artefact contains so many international influences. The sea that creates an island identity is simultaneously a road for communication, culture and trade.

The coble represents a fishery that was sustainable over many centuries. Monks on Holy Island in the 1300s employed fishermen and bought gear which included ‘cobles’ and ‘smalynes’ with 700 hooks, and caught most of the same species that were being caught in the early 20th century. There are a number of reasons for this. First, the coble’s size was self-limiting; only small amounts of gear could be used and small catches taken. On many days a coble could not fish at all. Secondly, coble fishing required an intimacy with the sea bed that was handed down. Fishermen learnt to recognise particular ‘ground’ by lining up ‘marks’ – distinctive features on land. Over generations, they mapped the sea floor with reference to events from their community, enmeshing their own stories with those of the natural world. It was in their interest to ensure that the catch was there for the next generation.

Sustainability, however, came at great human cost. Fishing from a sailing coble was dangerous. Many lives were lost. Close dependence on the natural world was also economically unpredictable. Most of all, line fishing placed a terrible burden on women’s lives. Women were heavily involved in many land-based aspects of the coble, especially selling fish and baiting lines. Every hook required at least one mussel. Bait had to be gathered from the rocks, carried home and ‘skyened’ (shelled), then placed onto 1,400 hooks every day. This work was gruelling, unpaid – and inescapable.

In Northumberland, engines replaced sails in cobles after World War I, and long line fishing ended around 1950, replaced by less sustainable methods, such as seine-netting and small trawlers. Very few cobles still fish from Northumberland, now mostly potting for crabs and lobsters. No new working coble has been built in Northumberland since the early 1990s. They have been superseded by fibreglass vessels of ubiquitous design, with more powerful engines. These boats preserve some aspects of coble culture, but tend to fish more intensively. They often deploy electronic plotters and echosounders alongside or instead of inherited knowledge. In contrast to the community surrounding a coble, they may be operated by just one man.

Without sentimentalising the harsh realities of long line fishing, we believe that the coble represents a way of life that connected people more intimately with the natural world, and through it, to each other. As such, we believe that the coble does not merely represent the past, but carries important lessons for a sustainable future.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- The Coble and Keelboat Society

- The Northumbrian Language Society and https://northumbrianlanguagesociety.co.uk/

- K. Porteous, The Bonny Fisher Lad (The People’s History, 2003)

- J. Salmon, The Coble, with commentary by A. Osler, Coble and Keelboat Society Reprint, 2008

- B. Griffiths, Fishing and Folk: Life and Dialect on the North Sea Coast, Newcastle, 2008

- A. Osler, The Curious Case of the Grace Darling Coble, Archaeologia Aeliana 5th ser., 37 (2008)

- A. Osler, The Salmon’s Kingdom: net fisheries of Northumbria, Maritime Life and Traditions no. 25, Winter 2004