We want to take you to Southern Oman, and into the practice of desert tracking, as described in two endangered Semitic languages: Mehri and Shehret. The word śaf in Mehri (śɛf in Shehret) means ‘unexpectedly, it turns out to be’ and is closely related to words meaning ‘track; print’: śaff in Mehri (śɛf in Shehret). Khalid Ruweya al-Mahri, a Shehret speaker, and Mehri colleagues helped us to understand this relationship. Tracks, like fingerprints, reveal an indisputable identity that may otherwise not be recognised. My fingerprint is unique to me, and my footprint is likewise unique. In the desert from afar you may believe you are following a camel from one herd, but on close examination of the tracks of that animal discover you are tracking a camel from a different herd. The track, therefore, reveals the unique identity of an animal or a person, and by extension śaf has come to be used where an action, object or event that was originally thought to be one thing unexpectedly turns out to be something else.

Younger speakers in Southern Oman might use śaf in sentences such as: śīnək ḥaybīt əkabs ḥaybayti śafs ḥaybitk ‘I saw a camel I thought was my camel, but it turned out to be your camel’. But they might not appreciate the link between this turn of phrase and the vital social importance of tracking for Mehri and Shehret livestock herders in the past. The track reveals identity without ambiguity, and skilled tracking can be a question of life or death. Well-known trackers are able not only to identify their own livestock within a foreign herd, but also to distinguish the bare footprints of members of their community from those of outsiders. Shehret-speaker, Faisal al-Mahri, described a well-known tracker being asked whose footprints he saw in the sand. The tracker gave the name of a man who was believed at that time to be in Kuwait. His companion told him it couldn’t be that man’s prints. The tracker insisted he was right. When they returned home, it turned out the traveller had returned from Kuwait the day before. The tracks were indeed his.

In a recent discussion, a teenage Shehret speaker asked whether the word śεf came from śof ‘hair’. Ali al-Mahri, a bilingual speaker of Mehri and Shehret, explained this lack of awareness among young people living in the main town of Salalah as resulting from a lack of earth or sand paths in the town: tracks cannot be imprinted on solid asphalt. The progressive paving of the environment, as social, economic and environmental forces shape Mehri and Shehret society, mean that the activity and terminology of tracking is being lost.

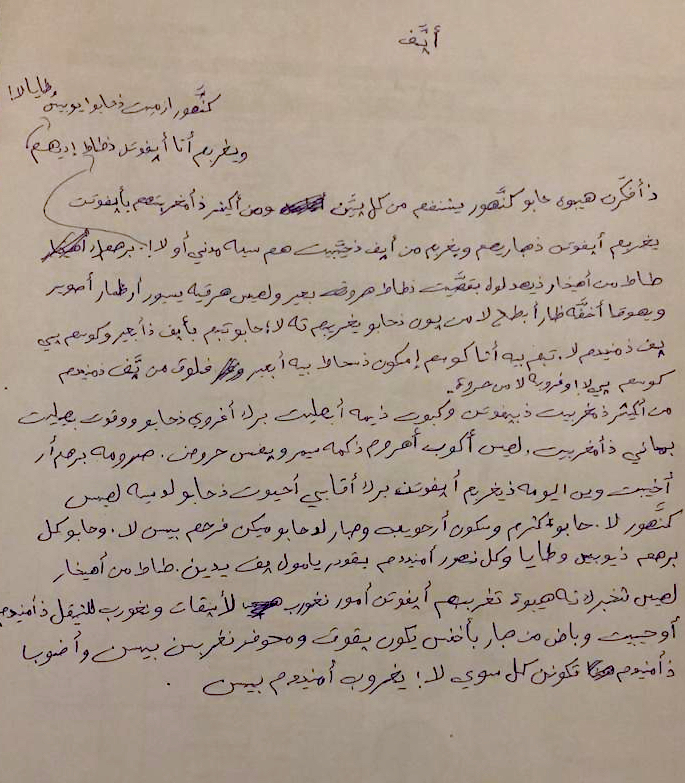

Śaff, Abdullah al-Mahri

In the past, people thought they could benefit from everything. From their deep knowledge of tracking, they recognised the tracks of their own camels, and they knew from a camel’s tracks whether it was pregnant or not. In the past, people didn’t wear shoes, and they could distinguish the prints of each other. I once heard an old man tell the story of someone who stole camels. After he stole the camels, that man just walked on stones. He deliberately didn’t place his feet on the earth so that people wouldn’t be able to track him. People followed the camel tracks, but they didn’t see any tracks of people. They followed the tracks to the place where the man slaughtered the camels. In that place where he had slaughtered the camels, they searched for people’s tracks but didn’t spot anything. So they had absolutely no idea who it was who had slaughtered them. From people’s deep knowledge of tracking, that word entered the Mehri language and a word emerged with the meaning of ‘knowledge’. As you could say, for example, I think that tree is a sīmər tree, but it unexpectedly turns out to be an Acacia tortilis tree. Nowadays very few people have the ability to identify tracks of camels and people. I think this is because people’s lifestyle is no longer like it was in the past. There are far more people, and they live in towns. And now people aren’t as keen on camels as they were. Now people all wear shoes and they can make new prints from the shoes that they wear. One old man when I asked him how he was able to recognise the tracks of camels and people said, ‘We know them from the stride of the person or the camel. We know how heavy the person or the camel is. And some camels’ tracks have splits or have hollows. We know them from that. And in terms of people’s toes, people all have differences in their toes. They are all different. We can identify who it is from their toes.’

Thomas de Burgh – 2012 – Halma, Oman www.nomadsinoman.com

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- Centre for Endangered Languages, Cultures and Ecosystems (leeds.ac.uk)

- Modern South Arabian Languages | School of Languages, Cultures and Societies | University of Leeds

- THE DOCUMENTATION AND ETHNOLINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF MODERN SOUTH ARABIAN | Watson C E Janet

- Bibliography of Modern South Arabian Languages (PDF; 0.5MB)