Neville Gabie and I met about 10 years ago, when we were both at the Cabot Institute at the University of Bristol. I was the new manager there, and he was our first Artist-in-Residence, supported by the Leverhulme Trust. Neville brought a quiet and thoughtful presence, a fantastic listening ear, and a history of inspiring, participatory projects from Greenland to Antarctica (and many places in between). I brought my passion for interdisciplinary thinking and working, and a mental Rolodex of the brilliant researchers that spanned the Cabot Institute’s environmental remit. It was a good pairing.

We both moved on from Cabot, and stayed loosely in touch, but didn’t really speak until late in 2020 when the call for the British Council’s Creative Commissions for COP26 came out. Throughout 2020 I had been thinking about trying to find a softer response to the environmental crisis. I have been on many protests, lent my voice to chants of “What do we want? Climate Justice! When do we want it? Now!”, voted Green, put posters in my window, and ear-bashed my friends. But in the dislocation of pandemic lockdown I felt myself wanting to respond to a quieter yet insistent voice that yearned for less shouting, and more acknowledgement of our beautiful, fragile relationship with the natural world.

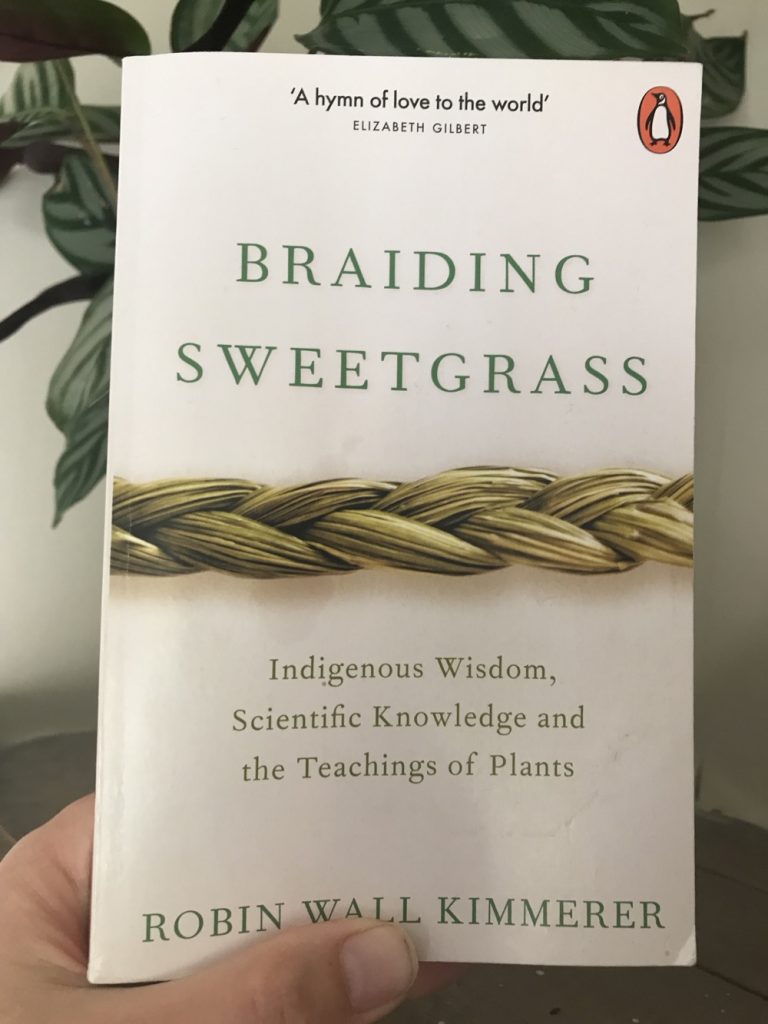

Words for what I was feeling came from the quietly dazzling book ‘Braiding Sweetgrass’ by ecologist and academic Robin Wall Kimmerer, a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. Author Elizabeth Gilbert calls the book ‘A hymn of love to the world’ and I agree. But even more it’s about a duet; Robin writes about the back-and-forth, the weaving of reciprocity between humans and more-then-humans. Not just relationships with plants and animals, but with and between fungi, lichens, stones and rivers. There’s the giving and the taking on both sides, an ebb and flow of energy, care and attention, that is shared through the idea of the Honourable Harvest. And there’s the energy and meaning that is conveyed in words, in the specific language that belongs to a place. Robin says, “To be native to a place we must learn to speak its language”.

With this book, I breathed out, and a space for doing the work I wanted to do appeared. And in that space I met Neville again, whose work was taking him along similar lines. Read how experiences with Noongar elder Cathy Yarran, and with Jessie Little Doe Baird and the Wampanoag community shaped his thinking.

Through our conversations came the seeds of living-language-land, and now, the time and the funding to support it.

To finish with another quote from Robin in a recent Guardian article – “People can’t understand the world as a gift unless someone shows them how”. I don’t know exactly how to do that, but that’s the energy of this project – sharing, revealing and exploring what is common to all of us but sometimes out of the frame. I look forward to learning together.