We know that it is possible to learn a language using a dictionary, a grammar or by taking a course. As we dedicate more time, we learn words, a basic vocabulary and sufficient pronunciation to enable us to understand and speak. We all learned the mother tongue of our family when we were toddlers, but only very few of us looked for the meaning of this language, and of its importance in influencing our lives. To undertake this search is to embark on an exceptional journey which can transform our entire life. This is a journey I have lived in investigating the words of my own language, Nehluen.

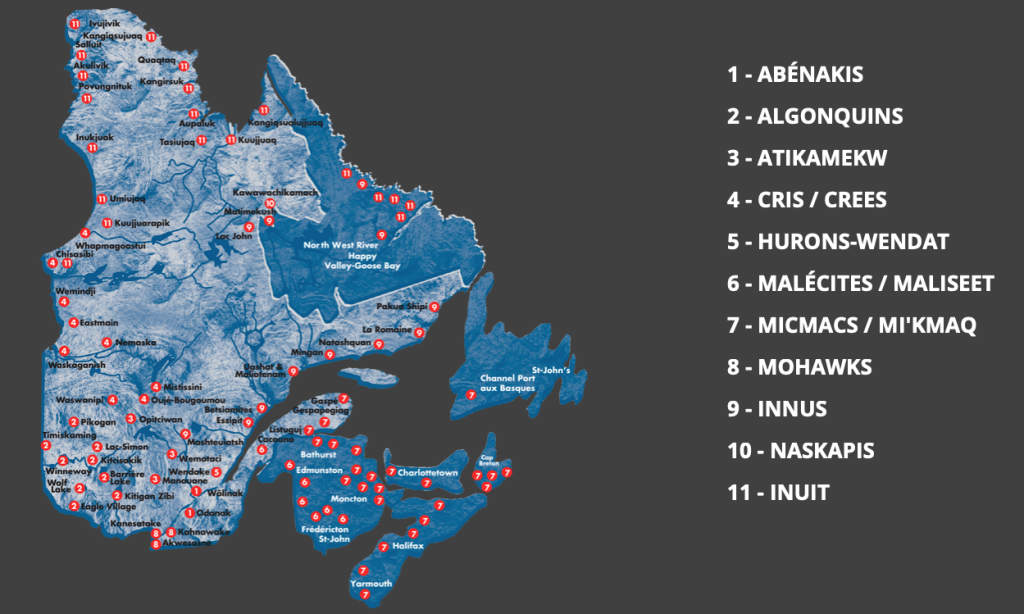

This is the common language used throughout the Innu communities in the province of Quebec, Canada, from Lac St-Jean to Labrador, passing by the lower Côte Nord. The Innu alphabet is based on 11 consonants and 7 vowels. It is indeed a complex language to learn by a new student, but so rewarding because it is so pictorial. The words represent more than a simple concept; they create a picture, a scene, animate a thought, define a precise action linking it with the environment. The Innu words are very exact, descriptive, and full of life.

The underlying reason is that there is one vocabulary adapted for village life and another one for the bush. These nuances are linked with the corresponding environment, which itself is indissociable from thought, and therefore the verbal expression. Since the landscape changes as we move from the South to the North, and from the East to the West, we also see it is reflected in the words used to designate the specific features of each place. It is in fact this precision of the words that enables us to understand the relationships which exist between the flora, fauna and the animals who live there. The human being must adapt to the decor, as he is a part of it. He is included in this big circle where interdependence prevails.

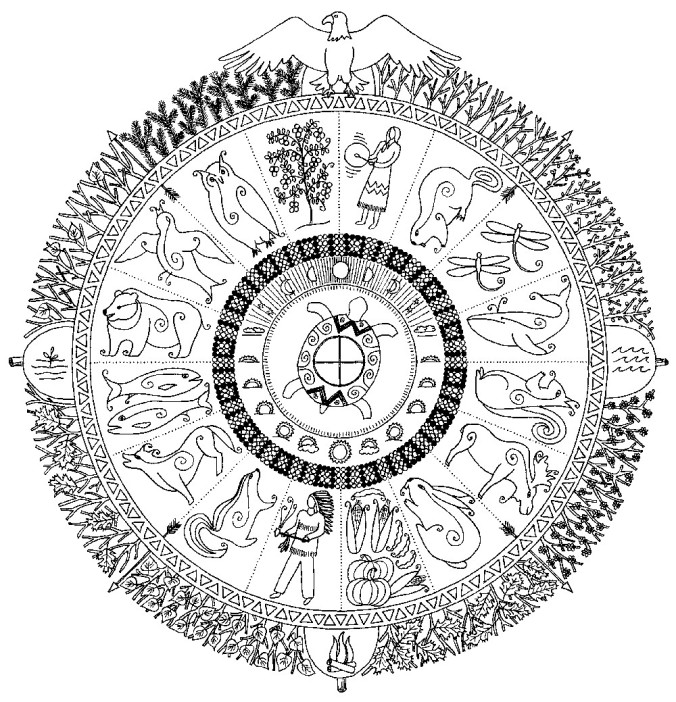

To better understand the base of the Innu language, we have to position ourselves in the context of circular thought. A human being and his environment are indissociable in this kind of thought. The pronoun ‘we’ will serve as an example to better understand the possible shades. If I wanted to speak of ‘we’ which includes me and you (singular or plural), then I would use ‘TSHINANU’. The prefix ‘TSHI-‘ corresponds to you in all its forms. If I wanted to speak about ‘we’ but in a way which is excluding you, whether singular or plural, I would say ‘NINAN’ (with the accent on the second N). Tshinanu – the inclusive form of we – invites sharing, community life, as there are no fences in the word tshinanu. It is a collective ‘we’, an open hand extended to others, inviting them to be a part of the circle. It also correspondingly tells a story, the story of the community of life of the person who speaks or writes. This word brings into relation the land, the animals, the plants and the peoples in the same pronoun.

The exclusive ‘we’ (NINAN) represents the person who is speaking about something, but without the listener or the group of listeners. Take, for example, a hunter who speaks about the moment when he was alone with the deer. He’ll say NINAN because, of course, the listeners weren’t there with him at that exact moment with the deer. The precision of the word thus conveys a very clear picture of the message, defining the role of everyone in the described scene. Speaking a language is a lot more than using words, as it also defines identity and belonging. It draws a portrait of the person’s native origin.

To speak of the area in Quebec inhabited by the Innu peoples, we use the word Nitassinan (our land), which also speaks to our inside land, our roots. For the traditional land of our families in the bush we say Nutshimit. It represents the land of silence, the inside discourse, the place of personal discovery, without any pressure. When presenting oneself and giving the name of the person’s community, people have an idea of the individual through the territory, which in turn speaks of a particular culture and way of life of the people living there, whether nomadic or sedentary.

When an Innu person is cut off from his/her territory, it deeply severs the bond to his/her identity. It means a loss of living roots, like becoming a stranger to him or herself. As a result, the words, loaded with context, lose their bearings in the new environment, there is no more silence, there are no roots. It is exactly this kind of broken bond, this deep wound that best describes placing indigenous peoples in reserves and residential schools, and healing will only be found by a return to the tradition. Let’s remember that the survival of our nations following these traumatic events rests on the shoulders of our elders who proudly protected our culture through the oral tradition. Our environment is the land, the forest, the plants, the insects, the animals, the water, the air and the human beings who are the stewards of the creator’s gift. An interdependent circle of life. From generation to generation, our teachings say that the earth doesn’t belong to us, but rather we belong to her, bearing in her our own distinctive roots.

Tshinashkumitin Iame

Missinak Kameltoutasset

A community celebration in Mashteuiatsh, Quebec in 2018

Marie-Emilie leads the ‘blanket exercise’ to engage people with the experiences of First Nations people.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- Learn more about the Innu people from the Canadian Encyclopedia

Chalay

The practice of chalay (or chhalay) embodies the Andean concept and value of reciprocity. It represents an ancestral alternative economic system which values, people, land and the sacred nature of food. Reciprocity is found at the heart of all relations, such that there are exchanges between people and mother earth, the apus (sacred mountains), plants and animals.

Historically in the Andes, non-monetary exchange has been linked to the ideals of economic and ecological complementarity, and contributed to self-sufficiency, not to economic gain. Although Andean farmers are now integrated into modern monetary economic relations, chalay continues to provide access to important goods and services without money. The farmers who practice chalay exchange foods, calculating the value of the products. In this case, value is not equivalent to the monetary value; rather it considers the time and effort for production, transportation, and takes into account the social relations between those doing the bartering, and the needs of the participants. The exchanges strengthen the relationships between family members and friends from different agricultural zones. Foods and seeds are also members of the family. When seeds are exchanged, the new seeds become ‘daughter-in-laws’. These new family members need to be treated with great care and respect so they will produce well.

I make chalay with corn seed. For the paracay variety, I make chalay with other women from the Rosaspata community. For seeds of the qello uwina variety I make chalay with women from the Ccachin communities. When I do chalay and exchange information on how to raise the seeds, we adopt them into our family, this helps the seeds from other places to adapt well to the land of my community, so we get a good harvest of corn.

Basilia Quispe Fernández

People who live in the middle zone, where there is maize, wheat and beans and there is little potato production, desire the delicious potato from the higher zones, as well as chuño and moraya (two kinds of freeze-dried potato). Those from the high zones desire the rich diversity of maize from the middle zone. From these two zones, they can also exchange for aromatic plants, fruits and vegetables from the valley. In this way, the families of the three zones exchange their products to diversify and balance their daily diet, and improve the nutrition of their children.

Chalay respects the sacred nature of food. Maize and potato are the source of life. They are for food, to sell, to trade for other products, to work in the fields. When taking the seeds to the market or another place, they smoke them in ritual, calling on Pachamama, asking her not to take the spirit of the plants, asking for them to remain in the community. When bringing new seeds into the home, offerings of coca leaves are made and they are sprinkled with chicha to welcome the seeds to their new home. Exchange in chalay is seen as an important part of the life journeys of the seeds.

Our Apu, sacred mountain, is the snow-capped Ccolque Cruz, with whom we do chalay in the month of August, which is carnival for our animals, for the cow, alpaca, llama. We make an offering to the Apu as a chalay, to help take care of our animals, so that they do not get sick. These times a disease has appeared that is killing our animals. Before we had more animals in this sector of Mapaccocha, many alpacas, llama sheep, and wild species such as llullucha (edible bacteria), now there is little llullucha and fewer animals.

Saida Juares Mamani from the Mapaccocha sector

In the barter markets (Chalayplaza), people used to bring many different products, including dry alpaca meat, wool, leather, and ceramic or iron products, but the conditions are changing. Some products, like salt or sugar, are almost fully integrated into the monetary economy. Some resellers of food products participate in the barter markets and try to exploit or trick the farmers. In these cases, the exchange is no longer respectful or just.

ANDES and the indigenous communities of Lares recognize the importance of chalay, and are researching the evolution of the chalayplaza over the past 20 years. During the research, local community members expressed an interest in protecting and promoting the practice of chalay. In June 2021, a municipal ordinance was approved to recognize the importance of the barter markets:

“Declare the practice of ‘Chalay’ or Traditional Exchange of Crops and Seeds, which takes place in the market places of Hinopampa, C.C. Choquecancha, C.C. Q’achin and C.C. Huacahuasi, as an Expresion of the Immaterial Cultural Heritage of the District of Lares, which contributes to the conservation of agrobiodiversity and food security of the local population” .

Ordenanza Municipal No004-2021-MDL, Lares, 15 de junio del 2021

Another reflection of the interest in protecting the barter markets is a new collaboration between two Biocultural Heritage Territories, The Potato Park in Pisaq and The Chalakuy Maize Park in Lares. Members of the two parks, together with Asociacion ANDES, are working to preserve ancestral knowledge and practices related to the Andean landscape and food systems, including chalay.

I do chalay in the Choquecancha market, we’ve always done chalay here. I have been doing chalay since I was young. Chalay is very important to exchange food products, to balance our diet, you don’t use money and that helps my budget. I am very happy because now more people are coming to barter. Like the communities of the Potato Park, I want the chalay to be more frequent.

Simeona Huillca Betancurt

Full list of contributors

Asociacion ANDES

Tammy Stenner

Parque de la Papa

Jhon Ccoyo Ccana

Ricardina Pacco Ccapa

Aniceto Ccoyo Ccoyo

Nazario Quispe Amao

Lino Mamani Huarka

Mariano Sutta Apocusi

Ciprian Ccoyo Banda

Bacilides Jancco Palomino

Daniel Pacco Condori

Parque Chalakuy

Ricardo Pacco Chipa

Juan Víctor Oblitas Chasin

Alberto Condi Durian

Saida Juares Mamani

Alfredo Hancco Santacruz

Maritza Churata Ttito

Basilia Quispe Fernández

Simeona Huillca Betancurt

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

Maloka

The ancestral and spiritual longhouse of the Murui-Muina, the Maloka, houses multiple families who cook and hang their hammocks in separate spaces. It is where the men chew coca and tobacco and where the women prepare sweet yuca, and where the elders gather to discuss and manage the affairs of the community. It is also where the dance of the Yadico (the Dance of Unity) takes place. In this process, which takes 15 days to prepare and lasts through the night, the Murui endeavour to heal the tensions and disagreements that arise within and between their communities. Resentment and discord are dissipated and the community re-weaves its harmony.

At the same time, the whole community gathers to strengthen and heal its intimate relationship with the natural world, and transmits the ancient wisdom and practices to their children and young people.

As one leader says:

We dance to achieve harmony with nature. In this sense, we bring the spiritual world closer to our people. The dance masters are knowledge-keepers who have an understanding of the environment and its changes; when they summon a dance, they are doing so for the health of our people, because these dances cure the illnesses that are present in our territories.

We dance to share our knowledge with our children and youth. These dances serve the purpose of uniting the people and families that are dispersed in our lands, thus strengthening solidarity and harmony in our communities.

Around 1,100 Murui-Muina people live in 5 settlements (resguardos) along the Caquetá river. Although their rights are officially recognised, deforestation is creating huge threats to their efforts to preserve their culture and way of life. Legal and illegal gold-mining, cattle ranching and the illegal drug trade are increasingly invading and fragmenting the forest on which they depend for water, food and healing herbs, while their young people are drawn into working for drug cartels and mining operations.

The fate of the forest, and the fate of the Murui-Muina people are intimately bound.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- Heirs of the Boa: a short documentary film that highlights the Yadico dance of the Murui-Muina people

- Colombian Television Programme ‘El Buen Vivir: Thinking and Acting Well’ (featuring the Murui people at 16:30)

- El Buen Vivir: a multiplatform project of the National Commission for Communication of Indigenous Peoples, CONCIP (Spanish: Comision Nacional de Comunicacion de los Pueblos Indigenas)

Wíyukčaŋ

This contribution is edited from a series of conversations with Tiokasin Ghosthorse, project producers, Neville Gabie and Philippa Bayley, and fellow contributor Malcolm Maclean.

Neville: As you have described it, Lakota is a language of verbs because everything in our world is alive, in motion, active. That idea completely changed my thinking because suddenly I could no longer see a tree as passive, but as actively being – ‘treeing’.

Tiokasin: If you see something in motion and suddenly it stops then you have to noun-ify it and it does not have any life – it does not have any motion… It becomes ‘a thing’. To think in the ‘earth paradigm’ (rather than in the ‘human paradigm’) – when you are seeing something in motion it is a more alive way to see and feel something because you are part of it. Your eyes are actually a part of that energy of motion, so you describe it that way. And then you describe the energy that you are feeling. So these two ways of understanding – motion and energy – are probably as close a way of getting to say how the language is structured.

The English language is not effective enough because we use concepts which are very basic building blocks. Concepts get in the way. Concepts put barriers in the mind and in the spirit too.

Neville: I remember you were saying that the human body and the trunk of a tree have the same word in Lakota – čaŋ. Can you say more?

Tiokasin: čaŋ is a tree – so we are talking about a torso, we are talking about the finger, the arm, and our hair is the leaves, you can go on, and our toes are the roots. It’s not just that your body is a tree – it’s the wíyukčaŋ – knowing, consciousness. You hear the čaŋ in it? So, in Lakota thinking, when you fragment the word: wí-yu-kčaŋ… Wí is the sun and to us, sun is a verb – it is being and it is always alive. And the yu is like the consciousness that is given to the tree and the tree is acknowledging the sun. This is not just us as the body of the tree, but this is the tree of who we are. We can spiral out into a bigger thought: Wow, the consciousness of the sun is the consciousness of the tree and vice versa. And we are the acknowledgement of it because look how we are made. We don’t have the language for that in English. I am speaking so many English words to describe one little thing!

Wíyukčaŋ – that’s knowing, consciousness – the wíyukčaŋ is also involving the moon and the stars and the trees of the earth and how they communicate, and we are in that as humans.

Philippa: You have talked about people becoming ‘technical human doings’ rather than ‘organic human beings’. Can you say more?

Tiokasin: In the older world, in the petroglyphs and hieroglyphs, you can see humans and nature; in some of the prophecies the Hopi have their feet below the ground as if they are planted. And the technical people are going nowhere, they are not planted. So that means their minds have become ethereal and disconnected. We are at a point now where there is still a chance for the majority to start thinking differently, more earth-oriented. There are a few who retain that sobriety with the earth. Otherwise we become intoxicated with our own humanness and get into the patterns of thinking we have superior intelligence, and that’s defined by concepts in the language.

It’s not progress to lose consciousness with the earth. Where is the language to keep that aliveness of the earth? You see how much confidence children have with the earth. They have a lot of confidence with the earth and then that’s torn down and replaced with false confidence. When my friends come from the more urbanized settings they are in nature and it’s all new and they are afraid of it, because they have no confidence in nature. So they will get their manuals out, so they can identify, but the butterfly is not thinking about identity.

When you are not confident with the earth, you lose your roots. But what I see is that as native people – we can wander but we know who we are. In the USA we are landless, we are landless as native people, but we are not homeless. Ok, temporarily we don’t have the land, but who said that we had it anyway? So those binding languages that are forcing you to say ‘you need to think this way – let’s make a treaty’ and yet history says ‘but where is your contract with the earth?’ That is our responsibility – being with the earth making sure that she is maintaining all life including the little human being.

Malcolm: That was a wonderful thing you said there about being landless, but not homeless. It applies in my part of the world as well. We have a famous poet here, Norman MacCaig, and I have to paraphrase it… ‘Who does this land belong to? The man who claims to possess it, or me who is possessed by it? ‘

Tiokasin: What if we thought in terms like that? You belong to the earth? And if you think like that then your language is confident. If you maintain a relationship with the earth, rather than control of the earth, that all life will be here. We started by saying ‘if we need the earth, does the earth need us?’ In a Western context we would say ‘of course we can save the earth; of course we can do this’ but that is an industrialized way of thinking and at the same time we are thinking she is going to flick us off like a flea. It’s not even a question. If the earth needs us because we are the earth it’s a sense of responsibility: ‘Yes, of course we need the earth, but of course the earth needs us.’ We are here in a relationship, so our language is all of relationship.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Getting started – Philippa’s thread

Neville Gabie and I met about 10 years ago, when we were both at the Cabot Institute at the University of Bristol. I was the new manager there, and he was our first Artist-in-Residence, supported by the Leverhulme Trust. Neville brought a quiet and thoughtful presence, a fantastic listening ear, and a history of inspiring, participatory projects from Greenland to Antarctica (and many places in between). I brought my passion for interdisciplinary thinking and working, and a mental Rolodex of the brilliant researchers that spanned the Cabot Institute’s environmental remit. It was a good pairing.

We both moved on from Cabot, and stayed loosely in touch, but didn’t really speak until late in 2020 when the call for the British Council’s Creative Commissions for COP26 came out. Throughout 2020 I had been thinking about trying to find a softer response to the environmental crisis. I have been on many protests, lent my voice to chants of “What do we want? Climate Justice! When do we want it? Now!”, voted Green, put posters in my window, and ear-bashed my friends. But in the dislocation of pandemic lockdown I felt myself wanting to respond to a quieter yet insistent voice that yearned for less shouting, and more acknowledgement of our beautiful, fragile relationship with the natural world.

Continue reading > “Getting started – Philippa’s thread”