This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- Connect with Violeta and Gaudencia on social media

- CHIRAPAQ, Centre for Indigenous Cultures of Peru

- CHIRAPAQ on Twitter

- CHIRAPAQ on Facebook

Kyká

The poem of Kyká, by Nicolás Acosta

The myth is recreated in the everyday, in the day to day, giving meaning to existence while walking.

Our people once again raise their houses, raise their spirits, their voices. In the infinite gaze that meets the glow of the sky at dusk and becomes breath the next morning. When the sun struggles to penetrate the multiform droplets of fog and smoke crawling through the straw of our ceremonial houses.

To be the hope of a people that walks the roads in daily activity, surprise filling every step in the amazement of another life that crosses the road, showing its colours of flight.

And in the cold kiss of the mother, it finds the cascade of illusion in the memory of the Grandmother, who greets and is recognised in the transcendence of her toothless smile.

It is our story that is also a song, raised in the humidity that shelters in the leaf litter that caresses the earth with its thick hands, but does not impede the sensitivity of the caress, the solidarity in the embrace.

The good thought and flirtatious smile that hides the food for the mother to multiply it in her life-creating action.

The territory feeds on hopes for the future. It asks for medicine to heal the people, the lake asks for water to bring babies, the stone asks for strength in thought. The river that flows with the freshness of life. Possums, foxes, rabbits, weasels, crabs and armadillos protect their existence in the underground that provides the raque tree, the myrtle, the hayuelo, the fern, the arboloco, and the frailejón plants.

While the prayer wakes the guard with all the grandparents and grandmothers, siblings, who in their resting place, feed their bones with the glow of the stars, radiating the feeling of our footprint on the hill.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- #soscerroseco: an active campaign to halt mineral extraction on sacred territory outside Bogotá. Search for this hashtag on Facebook.

- COLECTIVO DE EDUCACIÓN PROPIA PEDAGOGÍAS ANCESTRALES

- CONA – Pedagogías Ancestrales on Facebook

- Fundación Zaquenzipa: Wellbeing from ancestral thought (includes Spanish-Muisca dictionary)

Creating the story of |Xau

Read the full post about the word |Xau

Selection of artist works from the film of |Xau

Virginia MacKenny

(r) ‘Woodrose Explosion’ 2020 watercolour 29.5 x 23 cm.

Images copyright V. MacKenny

Ndaya Ilunga

Images copyright Ndaya Ilunga

Margaret Courtney-Clarke

(top right) The Ostrich Egg, Omaheke Region, Namibia, March 2019

(bottom) The Rain Dance #2, Omaheke Region, Namibia, October 2019

All images copyright Margaret Courtney-Clarke from her book ‘When Tears Don’t Matter’

Contributors to the film

- Prof Sylvia Vollenhoven – Script, Concept & Editing

- Ryan Lee Seddon – Cinematographer

- Kutelani Rasikhuthuma – Online Editor

- Prof Virginia MacKenny – Concept and Main Artworks: Of Holes and Things, Woodrose Explosion and Sharp Edged Grains

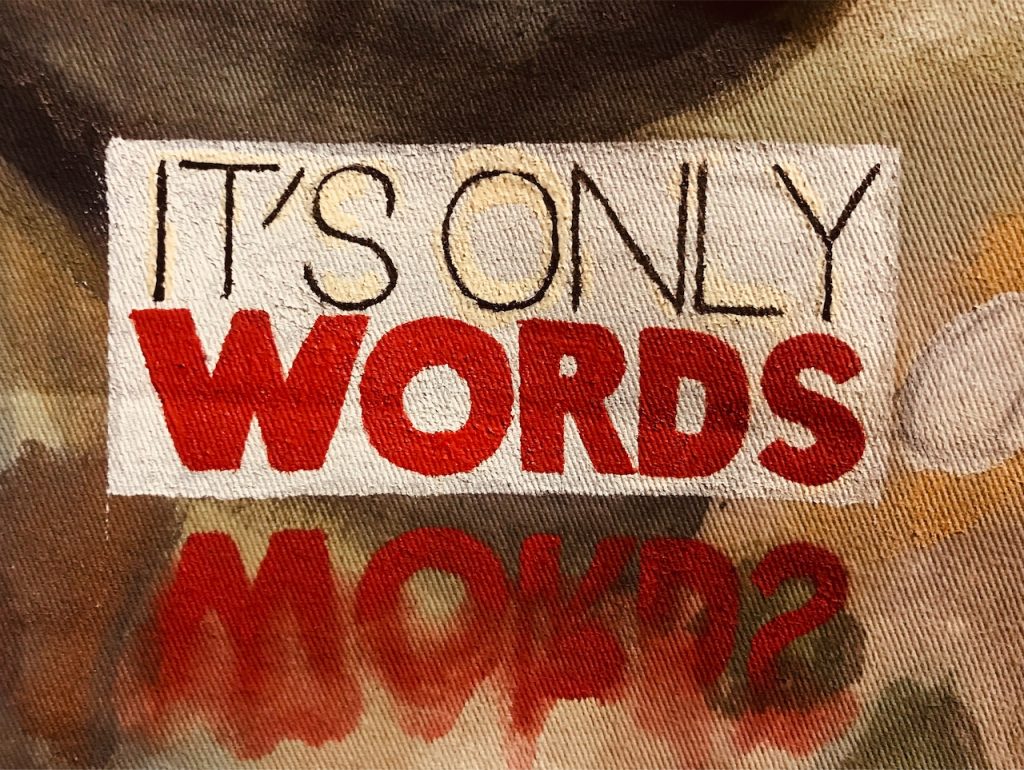

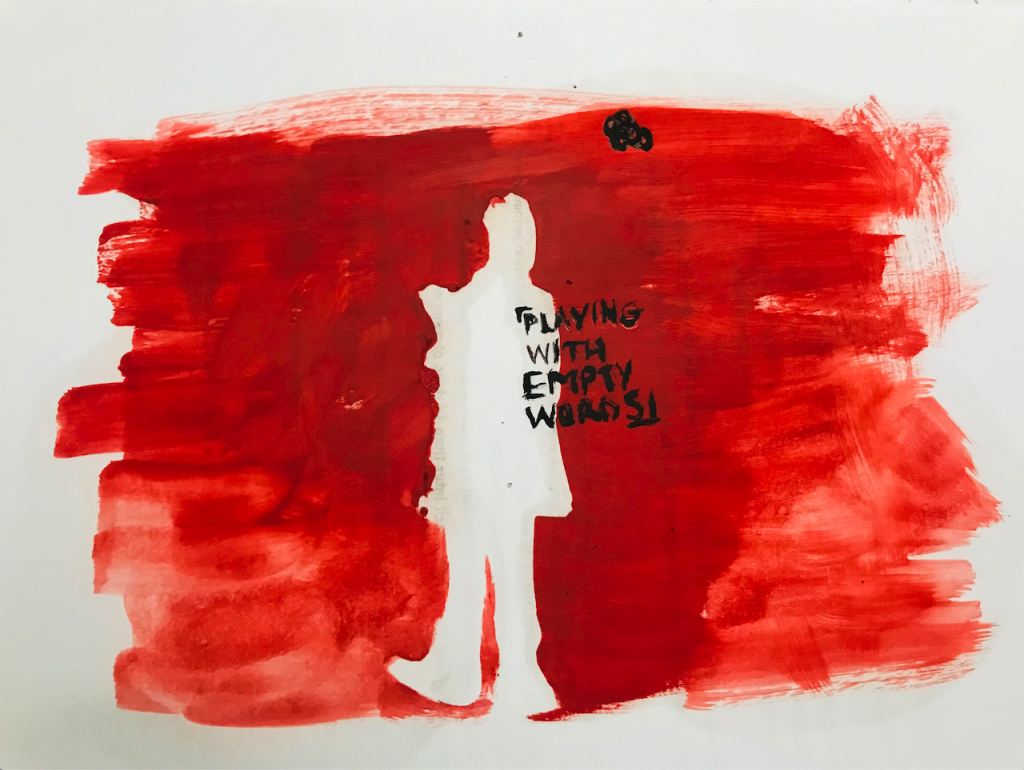

- Ndaya Ilunga – Word and Graphic Art: It’s Only Words and Playing with Empty Words

- Margaret Courtney-Clarke – Photographs from When Tears Don’t Matter and Archive Footage: Fire Dance

- Hilton Schilder – Music: Kalahari Thirst, Alter Native and eMail to the Ancestors

- Basil Appollis – Voiceover artist

- Bradley van Sitters, aka Danab ||Hui !Gaeb di !Huni!nâ !Gûkhoeb – Khoekhoegowab voiceover artist

|Xau

In the now extinct language of the |Xam Bushman people of Southern Africa |Xau or |Xaun meant to shoot with a magical arrow or go on a magical expedition.

My people had a word – No, more than a word – |Xau flowed through us – Lived in us – Connected us – Then it left us

When it went away – This word that is more than a word – It tumbled down the mountains – And out of our mouths – A precious possession… stolen, gone

Nothing has come to fill the vacant house of the |Xau – Magic does not live in the home of the new words – Disconnected broken arrows – Going nowhere

Our children play with empty words – That do not speak of mystical journeys

|Xau – My people had a word

|Xau – So much more than a word

|Xau – Melodies no longer heard

But deep in the earth there is healing – The land awaits our right doing – Ancestral Voices guide us back – To other Magical Arrows – And the melody of words that are more than words

To the |Xau of now

By Sylvia Vollenhoven

It is hard to restore our connections with the land, our love and respect of all that is, without finding the |Xau of now.

When I am a young girl growing up in apartheid South Africa my mother tongue is Afrikaans, a fascinating hybrid language with slave ancestry and the youngest on our Continent. It scoops up Asia, Africa and Europe in its arms and is closer to our hearts than English (the lingua franca of South Africa). When I am a young woman grappling with issues of identity, apartheid propaganda declares a version of my mother tongue to be the linguistic glue for driving the white Afrikaner people from racist nationalism to 20th Century nationhood.

For the mixed descendants of the colonials and the slaves (brought to South Africa mainly from Asia and other parts of Africa) our version of Afrikaans has been until recently the only tool we have had to build and solidify an African identity.

But now things are changing. We are going back into history to fetch precious intangible possessions that have been ripped out of our existence, out of our beings. There is talk of colonial overlords historically knocking out the front teeth of my people so that we could not pronounce the clicks of our indigenous languages. But in Southern Africa people are healing and relearning the languages that have survived, mainly Khoekhoegowab or its closest equivalent Nama.

The word concept |Xau, unearthed in an ancient dictionary, is a powerful example of what we have lost. The newer languages, inept by comparison, that have come to replace the rich indigenous lexicons do not have a word that comes close in meaning to “shoot with a magical arrow”.

When our languages were destroyed, we lost important elements of our culture and we lost entire civilisations. We have lost perspectives and a way of being in the world. Emulating a colonial way of expressing ourselves, our connection with the land and with the divine aspects of ourselves has been broken. This disconnect this brokenness, fuels self-destruction and in the process aids the destruction of the earth that sustains us.

Tumbling around in the maelstrom of the modern world, in search of what we have lost, we need to find those magical arrows. We need to find the |Xau of now to restore our relationship with the land and the divine within. Only then can we return to valuing the earth once more. Only then will we begin to heal what has been destroyed without and within.

Sylvia Vollenhoven is an indigenous South African author, playwright and filmmaker. Her seminal work on Khoesan identity, The Keeper of the Kumm, was awarded the nation‘s prestigious Mbokodo Prize for Literature and short-listed for all the major SA literary awards.

More about the |Xam language

The Language from which the word |Xau or |Xaun comes is |Xam (hear how to pronounce this word)

ǀXam is regarded by some as an extinct language of the Bushman people (a reclaimed and preferred term) of Southern Africa but its resonance can be found in modern Khoikhoi languages on the sub-Continent. The main, related modern language that has survived colonial devastation is Khoekhoegowab. |Xam was spoken by the ǀXam-ka ǃʼē people. This name or grouping was more a regional and geographic distinction than anything else. Much of the scholarly work on ǀXam was performed by Dr Wilhelm Bleek, a German linguist of the 19th century, his researcher sister-in-law Lucy Lloyd and their ǀXam-ka ǃʼē teacher informants ǁKábbo, Diaǃkwāin, ǀAǃkúṅta, ǃKwéite̥n ta ǁKēn, ǀHaṅǂkassʼō and other speakers. As a result, there is a surviving corpus of ǀXam that comes from the stories told by these individuals in the Bleek and Lloyd Collection at the University of Cape Town. Bleek’s daughter Dorothea added to the work, compiling a “Bushman Dictionary” that was published many years later.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages: Bringing Voices to the Future Through Living Dictionaries

Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages, a leading non-profit research organization based in the US with researchers located around the globe, stands at the intersection of linguistics and community activism. Our team has the capacity to launch technological solutions that help aspiring language activists and scholars alike. We are pleased to partner with living-language-land to help bring awareness to the issue of language endangerment leading up to COP 26.

Since 2005, researchers from the Living Tongues Institute have visited more than one hundred endangered language communities in fifteen countries. Since 2019, our team has reached over 200 more activists in 20+ countries through virtual events and workshops. Our researchers conduct documentary linguistic fieldwork, publish scientific papers, present at academic conferences, run digital training workshops to empower language activists, and collaborate with speakers to release web tools that benefit documentation and revitalization efforts. Our collaborators and teams have created more than 225 online Living Dictionaries to support threatened and low-resource languages. We have also provided free digital training sessions as well as technical and scientific support to many collaborators around the globe.

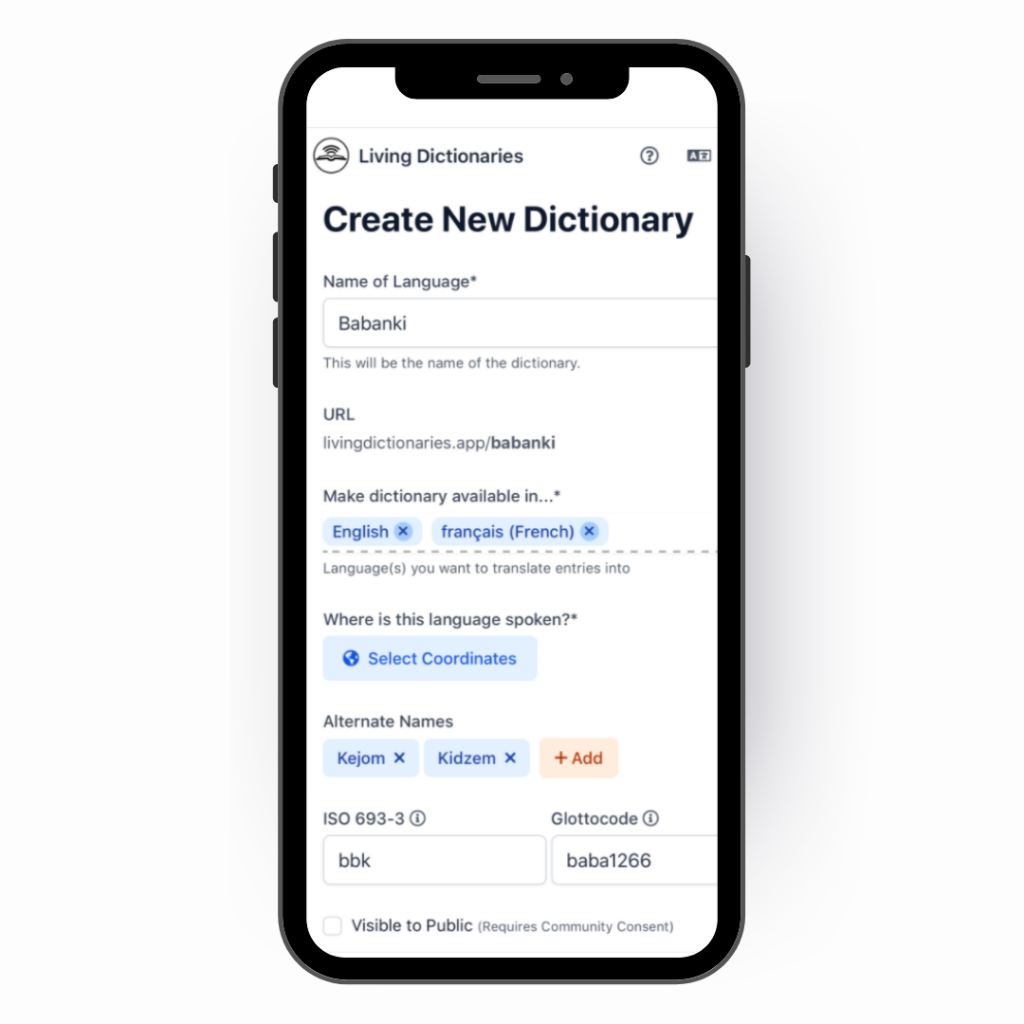

With over 3,000 languages in danger of being lost before 2100, we know there is a strong need for comprehensive, free online tech tools that can assist language communities. A moral imperative of the 21st century is the decolonization and democratization of linguistic resources. Online dictionaries should reflect the user communities, and citizen-linguists should have a primary role in developing them. Living Dictionaries provide a simple way to create high-quality multilingual documentation records.

As activists in the field of endangered language documentation globally, we know that colonization has caused thousands of language communities to become disenfranchised. Most countries are not investing in resources needed to support minority languages. Through the Living Dictionaries platform, we aim to obviate institutionalized barriers that prevent equal status and equitable treatment of all forms of linguistic communication. One of our main goals is to expand the online platform to serve all of the 3,000+ threatened languages in the world by 2050.

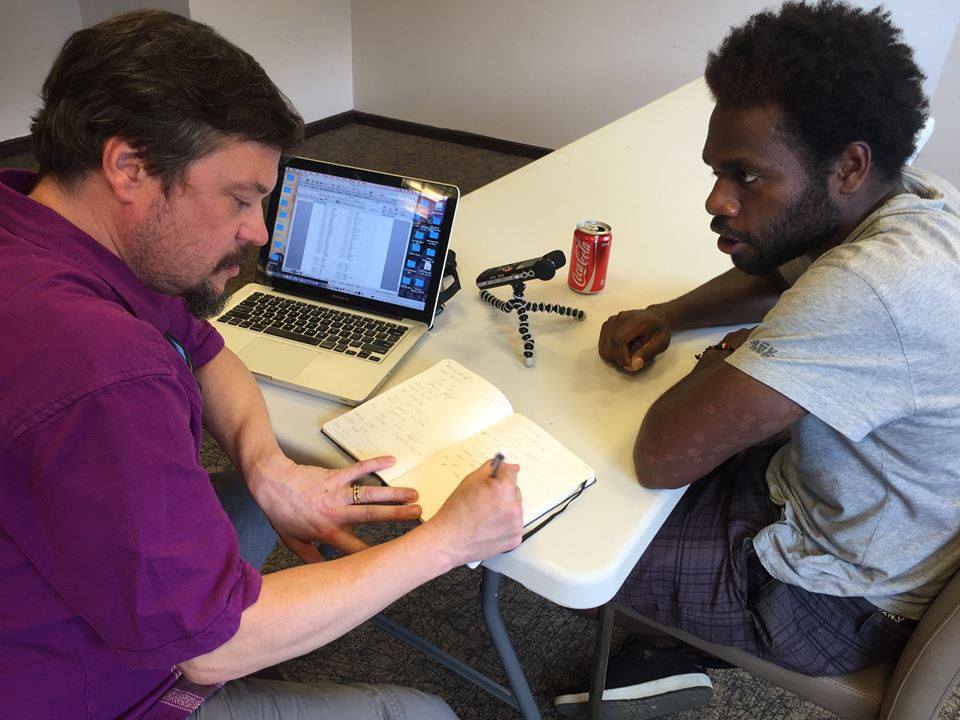

Dr. Greg Anderson and Martial Wahe build the first-ever Nafe online dictionary on Tanna Island, Vanuatu

Anna Luisa Daigneault interviews Ayoreo speakers Peje Picanerai and Ige Carmen Cutamijo in Paraguay

Mobile View of Babanki Living Dictionary Creation

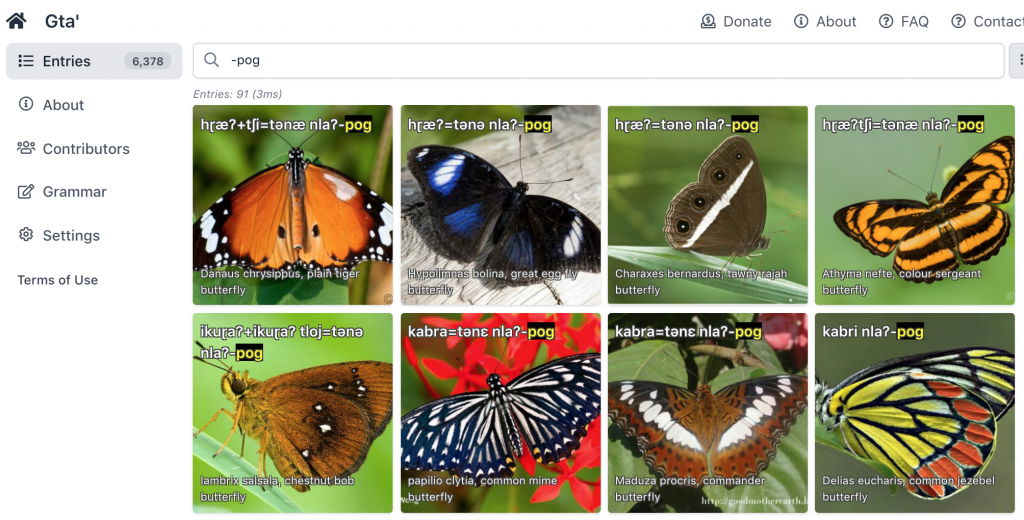

Gta’ Living Dictionary (India) -pog bug morpheme

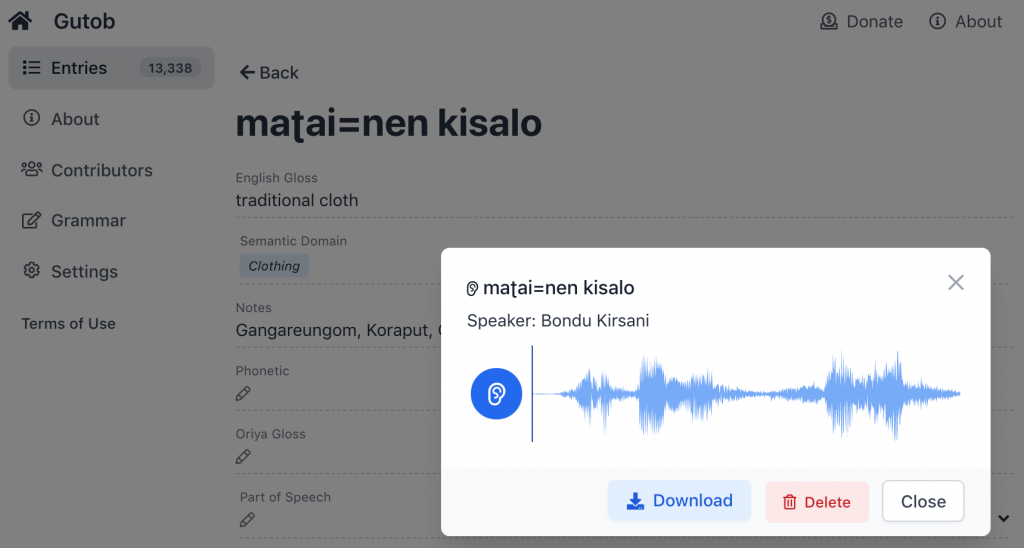

Gutob Living Dictionary (India) – Audio Waveform

The Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project

In 2019 I was lucky enough to make a short visit to meet Jessie Little Doe Baird and the Wampanoag Native American community in Mashpee, Massachusetts as part of an artist commission for the National Trust at Blickling Hall, Norfolk.

In the library at Blickling Hall we came across a Bible published in 1663, written in Wampanoag and known as The Eliot Bible, which had somehow found its way back to England. Eliot immigrated to Massachusetts just ten years after the Pilgrim Fathers and wanted to preach to the indigenous community there, hence translating the bible, significantly helped by a few Wampanoag people.

However, within a few short years of the Bible’s publication, the Wampanoag community was all but destroyed through war, enforced slavery and banishment. Speaking their language was made a crime, punishable by death. It became a lost, or at least underground language, where the only records were preserved in letters from the time and the Bible.

Continue reading > “The Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project”