The word immediately conjures an image in my mind’s eye. Narrow creeks at high tide, snaking through soft coastal marshlands. Bright crystal ribbons under blue skies, dark inky scrawls at dusk. Watery carvings in a shifting expanse of dappled browns, greens and gold.

A high-water fringe of tangled seaweed, crab carapaces, soggy seed heads and wispy plant stems, fishing nets, sea-chewed rubber balls, plastic shards and lost shoes.

And the birds. Always watching, waiting and following the tide as it silently fills and then empties the marshland – until the creeks become mud-reeking bobsleigh runs. Slick and treacherous.

In-between places. Fickle and fascinating. So still, somehow – yet forever on the move.

Slightly fearful places, at the edge of our comfort zone and confidence limits. Few of us will ever know and understand these places like the fishing folk of the Loughor estuary in South Wales who once used the named creeks – such as Gwter Gladys, Gwter Fawr, Gwter Cefn Sidan, Nant Grwnshir – to define their own, individual cockle fields far out in the bay, and to navigate safely across the marshes at low tide.

In the standard historical Welsh Dictionary the word ‘morfa’ is defined as a low lying wetland (usually by the sea) that is periodically inundated by water. A ‘[sea] marsh, salt marsh, fen, moor’. The dictionary notes that the word ‘morfa’ has also been used in the past for land that can become flooded along inland rivers – but only in one part of south Wales. The word ‘morfa’ literally means ‘a place of, near or shaped by the sea’.

Land reclamation, coastal development and other pressures over the past 150-200 years has meant that ‘morfa’ is often encountered as a toponymic ghost these days, haunting the landscape with a word-image of our past, but reminding us also of a valuable habitat that can help us tackle today’s climate challenges.

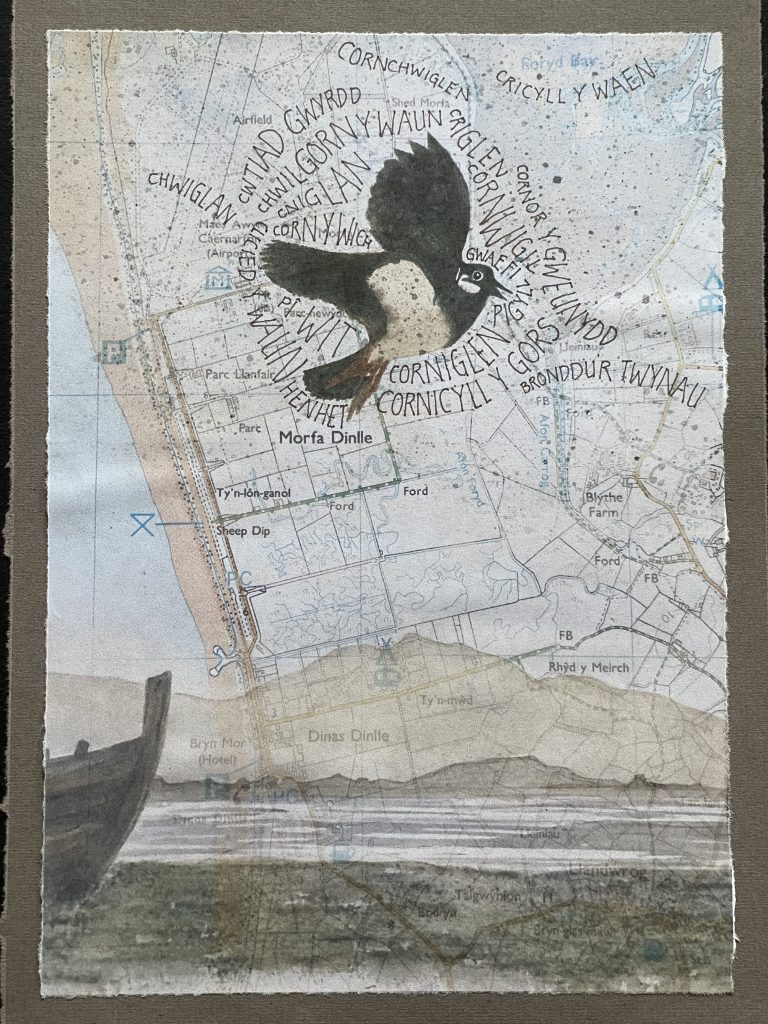

From my home in north-west Wales I look down on a ‘Morfa’. This place, called ‘Morfa Dinlle’ – which broadly translates as ‘the saltmarsh near Lleu’s hillfort’ [Ordnance Survey SH438 572], is an area of low-lying marshy grassland at the edge of the Menai Strait, a sea channel that divides the island county of Anglesey from mainland Wales. In this fragile, changing environment the lapwings (Vanellus vanellus) at Morfa Dinlle are clinging on, in one of their last breeding sites in Wales. This striking bird, with its distinctive call, was once common in Wales, and there are numerous accounts of people collecting and cooking lapwing eggs found in local coastal marshland and dune sites until the middle of the 20th century.

Morfa Dinlle was once part of the ‘great marsh’ that the Welsh antiquarian and naturalist Thomas Pennant mentioned as he travelled through this area in the 1780s. This ‘great marsh’ would have been a far more extensive mixture of saltmarsh, sand-dunes, bog, wet grassland and wet woodland than we see in today’s landscape. Most of the great marsh has been enclosed, drained and improved since the early 19th century but its former extent can still be traced through the names of fields, farms and fords in the area. One of the best resources we have in Wales to help with this kind of historic place name research is the National Library of Wales’ digitised database of 19thcentury tithe maps and accompanying schedules.

This section of coast is still changing, especially as a result of climate change. Nowhere is this more apparent than at a nearby prehistoric hillfort. This hillfort, called ‘Dinas Dinlle’ probably dates from the Iron Age. Perched on a cliff edge it is rapidly eroding and disappearing as the coastline retreats inland.

Dinas Dinlle hillfort

Looking southwards towards Morfa Dinlle and Dinas Dinlle from Abermenai (Anglesey)

The community archaeological dig at Dinas Dinlle for the Cherish project, 2019

Aerial view of Morfa Dinlle with the Dinas Dinlle coastal hillfort behind

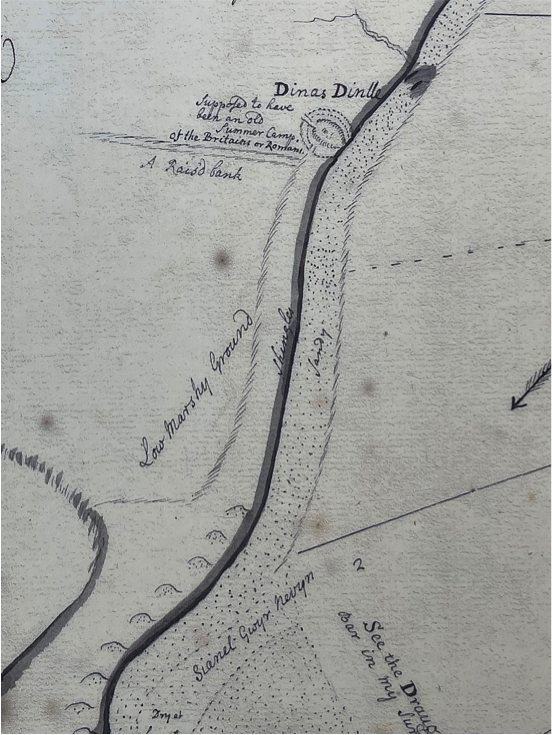

The same hillfort was drawn in beautiful detail by a renowned, self-taught Welsh hydrographer called Lewis Morris in the early part of the 18thC. It shows the Dinas Dinlle hillfort as being almost complete at the time.

Comparison between today’s aerial photographs from the Cherish project and the Lewis Morris map clearly shows how much the coastline has retreated in the last 280 years. The land that we now call ‘Morfa Dinlle’ is described on the Morris hand-drawn inky map as ‘low marshy ground’, fringed with a neat series of sand dunes extending out to sea. I look at this map and think of Thomas Pennant’s ‘great marsh’, and of Lewis Morris’ bold, brave effort to survey the coastline of Wales in the early 18thC. And more than anything I hear the lapwings’ wheedling, folorn cries – still calling through the years.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn more

- CHERISH project: Wales-Ireland coastal archaeological project

- CHERISH project: Dinas Dinlle and surrounding area